In a study published in Nature in 2002, Jonathan Chase and Mathew Leibold showed, through experiments in ponds in different watersheds, that the productivity-diversity relationship was scale-dependent. Among ponds within a watershed, the relationship was hump-shaped while across watersheds the relationship was positive and linear. Fifteen years after the paper was published, I asked Jonathan Chase about the motivation to do this study, his collaboration with Mathew Leibold and what we have learnt since about productivity-diversity relationships.

Citation: Chase, J. M., & Leibold, M. A. (2002). Spatial scale dictates the productivity–biodiversity relationship. Nature, 416(6879), 427.

Date of interview: Questions sent by email on 5th November 2016; responses received by email on 19th November 2017

Hari Sridhar: Correct me if I’m wrong but you early research work seems to have been mostly on food webs, What was your motivation to do the work presented in this paper, in relation to the work you had done earlier?

Jonathan Chase: I was playing around with some food web models that eventually became part of our Ecological Niches book by Chase and Leibold 2003. Mathew Leibold had been working on these models for some time, and had been testing various mechanisms for the ‘hump-shaped’ productivity-diversity relationship that he and others were finding in a number of different systems. I realized two things: 1) In the models, we might expect more variation due to priority effects (alternative stable states) at higher levels of productivity than at lower levels, and that this would lead to higher beta-diversity at higher productivity. 2) Higher beta-diversity at higher productivity might be able to help explain/resolve something that had been bugging me (and many others in the field)—that the hump-shaped pattern seemed to emerge more often at small scales, whereas at larger scales the pattern was more typically linearly increasing. So, I went out and collected the data in a nested way, and found just that. Hump-shapes at small scales, but linear patterns at large scales, because beta-diversity increased with scale. Of course, with these patterns, we had no idea whether food web dynamics were driving them, but it was all inspired from the sorts of food web studies (and in particular, the influence of predators on prey diversity) that I and Mathew were exploring.

HS: How did the collaboration between you and Mathew Leibold come about for this study? What did each of you bring to this piece of work?

JC: Mathew Leibold was my PhD advisor, and as I mentioned above, it was his models and local-scale data that inspired me to resolve what seemed like an enigma in the literature (i.e., different patterns emerging at different scales). We’ve both been working on these problems, sometimes together, off and on ever since.

HS: Why did you decide to do these surveys in ponds? Where were these ponds located?

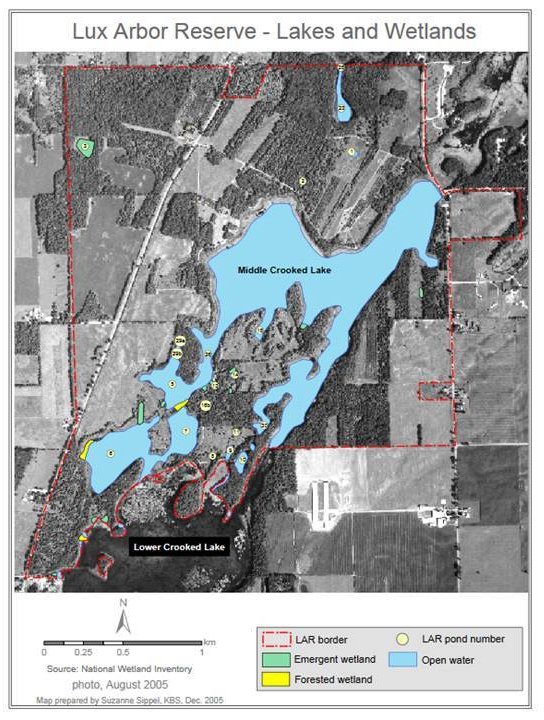

JC: I had been working in these ponds as a part of my PhD thesis, and Mathew and many others had worked in similar ponds. These were our ‘model system’ to explore patterns of abundance and diversity in food webs. The ponds were nested in various watersheds throughout south-western Michigan, near the Kellogg Biological Station of Michigan State University, where Mathew and his students had been working for some time.

Aerial view of one of the field sites (map prepared by Suzanne Sippel)

HS: Do you continue to work in these ponds? When was the last time you visited them? In what ways do you think these ponds have changed since the time you did this study?

JC: No, I no longer work in those ponds. When I moved to Pennsylvania, for a professor position, and then to Missouri, I found similar local ponds in those areas to do related work. But I haven’t really revisited those ponds since collecting the data for this paper, although I know others in Mathew’s group and other research groups have visited several of them in the context of other experiments.

HS: Could you give us a sense of your routine during the time when these surveys were being done? Were both you and Mathew Leibold involved in the doing the surveys? Did you have other people to help you during the experiments?

JC: I learned all that I know about pond sampling from Mathew and colleagues, and tagged along with him on several of his survey campaigns. For this particular project, I did much of the sampling myself, but Mathew and several others helped with aspects of the surveys.

HS: Could you tell us a little more how you knew the people you acknowledge and how they helped:

JC:

a. J. Shurin—Jon was a lab mate and helped with the intellectual development of the ideas and in just knowing about these ponds.

b. M. Willig—Mike commented on the manuscript and helped discuss a number of important problems.

c. M. Vandermuelen—Mark worked in my lab and commented on the manuscript.

d. P. Lorch—Patrick worked in my lab and commented on the manuscript.

e. T. Knight—Tiffany is a long-term colleague (and my spouse) and commented on the manuscript and helped discuss a number of important problems.

f. A. Downing—Amy was a lab mate and helped with the surveys as well as through a number of important discussions.

g. T. Leibold—Travis was an assistant in the lab, and helped with the surveys.

HS: How long did the writing of this paper take? When and where did you do most of the writing? Did you and Mathew Leibold meet/talk often during the writing of the paper?

JC: It’s hard to say how long the writing took, because it was among many other projects I was working on. Most of the writing was done while I was a post-doc at the University of California-Davis. Mathew and I were working on our Ecological Niches book, and so we met during the work on this manuscript, but much of it was in the context of our other collaboration.

HS: Did this paper have a relatively smooth ride through peer-review? Was Nature the first place this was submitted to?

JC: Actually, that’s an interesting story. I first submitted the paper to American Naturalist, with both the data and the food web model I was talking about above. The reviewers liked it ok, but felt that the model and data didn’t match very well, and so it was rejected. So, we chopped out the model and decided to go for Nature, where it was accepted (after revisions of course). We eventually published the model that went along with it in the Ecological Niches book.

HS: What kind of attention did this paper receive when it was published?

JC: That’s hard to say. I think it was pretty well received, because it made so much sense, and seemed to confirm what everyone thought was going on. It was just a nice way to synthesize what we already suspected with a single dataset.

HS: What kind of impact did this paper have on your career and the future course of your research?

JC: I’m not sure the impact on my career. Certainly having a Nature paper doesn’t hurt, and I’m sure it helped. But I can’t quantify how. However, for my future career, this paper certainly represented a turning point for me. I’ve been obsessed with the issue of scale and diversity ever since, as it provides such a rich ground for synthesis and understanding. We’ve come a long way in our analytical tools, but in essence, I’m still exploring very similar kinds of issues.

HS: Today, 14 years after it was published, would you say that the main conclusions of this paper still hold true, more-or-less? Could you also reflect on the generality of these conclusions as borne out by subsequent research?

JC: The main conclusion of scale-dependence in productivity-diversity (and many other relationships) certainly holds true. However, the answer isn’t as simple as we suggested—naturally. First, there are good reasons we found what we found, but there are also good reasons different patterns could emerge. For example, local patterns aren’t always (or even usually) hump-shaped. And there are so many different ways to measure beta-diversity and productivity, that people have found lots of different results. But in all, I think the idea that scale is critical for understanding diversity relationships is pretty well ensconced.

HS: If you were to redo this study today, would you do anything differently?

JC: Again, I’m still doing very similar things. The surveys would be quite similar, but I’d do the analyses a bit differently.

HS: This paper has been cited close to 600 times. At the time of the study, did you anticipate at all that it would have such a big impact? Would you know what it is mostly cited for?

JC: I was pretty proud of it at the time, but I’m not sure I’d know how big of an impact it would have. I think it’s mostly cited for the idea of scale-dependence in biodiversity response to productivity (and other drivers) and I’m pretty happy with that legacy.

HS: In the beginning of the paper you say “At regional spatial scales, considerably less theory is available.” Could you reflect on how that has changed in the years since the paper was published?

JC: To some degree, I think this remains true. There is ‘macroecological’ theory that explores larger-scale biodiversity gradients, but not the sorts of dynamical models that are used to understand local-scale diversity gradients. Macroecological models are cool, but rarely connected to community-dynamical models.

HS: You say “three primary mechanisms [could] cause species dissimilarity to increase with productivity”. Has subsequent research shed light on the relative importance of these different mechanisms?

JC: Yes, I published an experimental paper in Science in 2010 showing pretty good evidence for the ‘priority effects’ mechanism. This was based on a 7-year-long experiment in experimental ponds, where I manipulated nutrients and priority. However, not everyone agrees. In fact, Mathew Leibold still bets more on the ‘temporal turnover’ mechanism. In 2004, he published a paper with Chris Steiner predicting the sorts of patterns we showed that resulted from temporal turnover in a simulation model. And Steiner published a paper more recently also suggesting time played a strong role. And finally, others have found heterogeneity can also be greater at higher mean productivity, leading to these patterns. So, all of the mechanisms are valid and quite possible. In addition, some studies have shown the opposite effects, but these also make sense. For example, in some cases, increased nutrients can lead to lower heterogeneity and reduced regional diversity.

HS: In the last sentence of your paper you say “Understanding the scale-dependence of these issues will be essential in order to predict and ameliorate the effects of humans on the earth’s biota”. Could you reflect on the importance given to scale-dependency in human impacts on diversity, in the years subsequent to this paper?

JC: Yes, consider the current debate about biodiversity loss. We know biodiversity is being lost at an alarming rate from the globe. And we sort of naively assume that this biodiversity loss should uniformly translate at all lower scales. But recent meta-analyses (though controversial themselves) have indicated that biodiversity may often not be declining even when, regionally and globally, species are going extinct. Biodiversity is not a typical response variable, and has a great deal of scale-dependence that is quite difficult to quantify without great care. Thus, when we discuss human impacts on diversity, we must consider scale in this context.

HS: Have you ever read this paper after it was published? If yes, in what context?

JC: I think so. Mostly in the context of graduate seminars I was teaching…

HS: Would you count this paper as a favorite, among all the papers you have written?

JC: Yes, absolutely. It started me down a 15 year obsession with scale and diversity…

HS: What would you say to a student who is about to read this paper today? What should he or she take away from this paper written 14 years ago? Would you add any caveats?

JC: Scale matters in biodiversity studies, and it’s time to stop hiding that fact, and instead embrace scale-dependence as a way to understand how (and why) biodiversity varies from place to place and time to time. The only caveats I would add is that there are now much more sophisticated ways today to quantify the scale-dependence and the factors that underlie it.

0 Comments