In a paper published in Ecology in 1978, David Inouye demonstrated, using removal experiments and careful observation in Gothic, Colorado, that the use of resources by a bumblebee species is affected by the presence of other bumblebee species , a finding that suggested that competitive exclusion occurs in these species. Thirty-nine years after the paper was published, I asked David Inouye about his motivation to do this study, memories of field work and what we have learnt since about resource partitioning in bumblebees.

Citation: Inouye, D. W. (1978). Resource partitioning in bumblebees: experimental studies of foraging behavior. Ecology, 59(4), 672-678.

Date of interviews: Questions sent by email on 13 December 2017; responses received by email on 14 December 2017.

Hari Sridhar: I would like to start by asking you about the origin of the study presented in this paper. I notice you cite your PhD thesis a couple of times. Could you tell us how the work presented in this paper was related to rest of the work you did during your PhD?

David Inouye: I did my PhD research at the Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory (RMBL), mostly on resource partitioning in the bumble bee community there. That paper was from one of the chapters in the dissertation. At that time it was more common than it is now for research papers to be single-authored, and my advisor (Dr. Helmut Mueller) did not work on bumble bees and never visited my research site (he was back in Chapel Hill at UNC). I only did one experimental study in my dissertation, and that paper was based on it. Interestingly, another bumble bee researcher at RMBL (Berry Brosi) essentially repeated that experiment a few years ago, but in a more sophisticated context.

HS: Stepping back a bit, could you tell us how you decided to do a PhD on bumblebees?

DI: I started my Ph.D. work on hummingbirds, and spent most of my first summer as a graduate student studying time and energy budgets of territorial male Broad-tailed Hummingbirds. During that time I discovered that 1) bumble bees don’t get up at 5 AM, like hummingbirds, and 2) they don’t fly in rainy weather, as hummingbirds do. Also, you don’t need permits to work with them (federal and state permits are required to capture hummingbirds), for example for marking them (with paint) or gluing tags on them. So at the end of my first summer of research I decided to switch to work on bumble bees for the next three summers. There were also a few other graduate students at RMBL working on bumble bees then (Graham Pyke, Nick Waser, John Pleasants, and later James Thomson).

HS: This study was carried out in “an area 15 x 20 metres in the townsite of Gothic (elevation 2886 metres), Gunnison county, Colorado, USA” and “the Washington Gulch trail”. How did you choose these sites to work in? Do you continue to work in these sites today? When was the last time you visited them? In what ways do you think this 15 x 20 m area has changed since the time you did this study?

DI: There were relatively few people (compared to now) working at RMBL then, and no committee overseeing research projects (as there is now), and the Forest Service didn’t pay attention to RMBL researchers working in the Gunnison National Forest. I picked that plot in Gothic because it was close to my lab, and had a good mixture of the two species of wildflowers I wanted to use, as well as a good population of bees. The Washington Gulch trail, which starts further up the East River valley, was a site used by Graham Pyke for an altitudinal transect studying flower and bees, and I repeated his earlier survey as another chapter in my dissertation. We (Graham, James Thomson, and I) collaborated on a repeat of that survey in 2011 to find out how bees and flowers are responding to the changing climate (the queens are moving up in altitude).

HS: Could you give us a sense of what a typical day in the field was like during this study? What time did you work, how did you get to your field site, did you have people to help you etc.?

DI: One of the advantages of working at RMBL is that you’re living on site. During my graduate student years we were renting cabins from RMBL, and eating some meals in the communal dining hall. No running water in the one-room cabin, a wood-burning cook stove for heat, and no telephones in Gothic. One morning in spring we woke up to find lines of snow on our sleeping bag that had blown in through the cracks in the wooden walls (at 2,900m). It was a 2-minute walk from my cabin to my research lab, which was mostly used for storing field gear, and to the field site for that experimental study. I was usually out in the field by 8, and worked until close to dinner (6 PM in the dining hall when we ate there). There’s also an active seminar program at RMBL, and a group of grad students who often got together to talk, so a few nights a week scientists would get together. Towards the end of my PhD work I had occasional assistance. For my first three year in graduate school I had a fellowship ($300/month) from the National Defense Education Act, and in 1974 got an NSF grant for improving doctoral dissertation research in the field sciences. “Resource partitioning, niche breadth and niche overlap of bumblebees in two high altitude sites in Colorado.” 1974-76, $2,900. That helped to pay the summer field station expenses, and for occasional assistance I think. In 1976 I got my first real NSF grant, for work on an unrelated project (ants and plants).

Another important aspect of working at RMBL is that it’s always been family-friendly, so each summer my wife and kids would travel to CO with me. One son met his wife there, and is now (as a Professor at Florida State University, as is his wife) collaborating with me on some research projects there. My father was a physician and used to volunteer as a camp doctor for a couple of weeks in the summer as his vacation, to see me and my family. I now have a granddaughter spending summers there; I think her parents want to give her the experience her father had of growing up there in the summers.

HS: You acknowledge a number of people at the end of your paper. Could you tell us a little more about how you knew them and their contribution to this paper?

DI:

a. H.C. Mueller – Helmut was my advisor; an ethologist who mostly studied hawk behaviour

b. J.A. Feduccia – an anatomist and morphologist, faculty member on my committee

c. E.A. McMahan – Betty McMahan was an entomologist, faculty member on my committee

d. A.E. Stiven – Alan Stiven was an ecologist, faculty member on my committee

e. E.H. Wiley – Haven Wiley was another behavioural ecologist, member of my committee

None of these committee members was very involved in my research, although they provided feedback in my committee meetings and on the dissertation.

f. D. Morse – Doug Morse was a faculty colleague at the University of Maryland (where I started after finishing my Ph.D.), who also worked with bumble bees (in Maine).

g. B. Rathcke – Beverly was a fellow student on my tropical ecology course in Costa Rica (with the Organization for Tropical Studies). She was a few years ahead of me, and ended up being the editor handling my Ecology paper (and did a great job). Unfortunately she died a few years ago, just after retiring from the University of Michigan.

h. Rocky Mountain Biological Laboratory – the field station where I did my research, and have worked since 1971.

HS: How long did the writing of this paper take? When and where did you do most of the writing?

DI: The first version was a dissertation chapter. At that time it was not the practice (as it is now) to write up chapters in the form of publishable manuscripts, so I had to re-write it in a format more appropriate for a journal. My recollection is that it had to be shortened significantly. I might still have somewhere the earlier drafts of that paper.

HS: Did this paper have a relatively smooth ride through peer-review? Was Ecology the first place this was submitted to?

DI: Yes, Ecology was the first place I sent it. I can’t recall what the reviews were like (I might still have them in a filing cabinet at home, but I’m en route to Europe for 3 weeks). But I think it went through a couple of drafts with Bev Rathcke in her role as editor.

HS: What kind of attention did this paper receive when it was published?

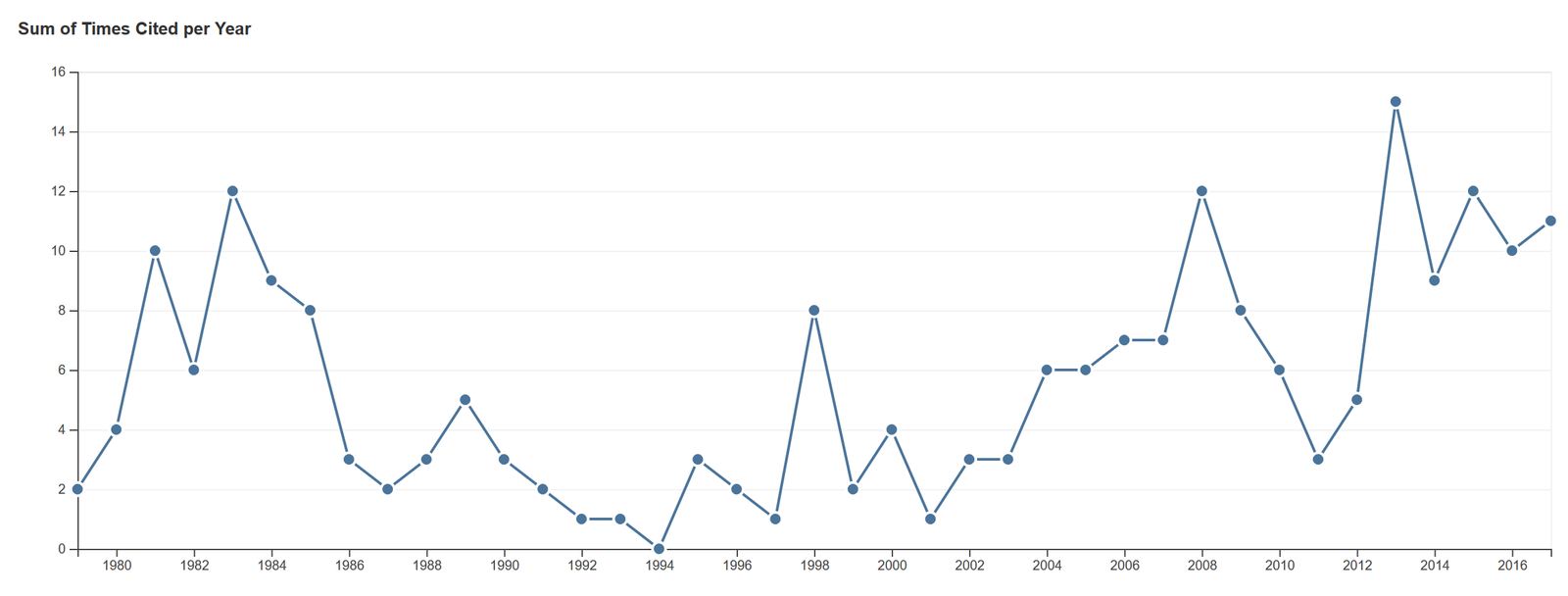

DI: Here’s a plot of the number of citations over time (from Web of Science). It’s my 6th most cited paper (297 to date):

I guess there was an initial surge of interest (competition and resource partitioning were relatively hot topics in ecology at that time), with a decline for a while, and then a renewed interest, perhaps because of the increase in use of bumble bees for studies in ecology and pollination in the past decade or so.

HS: What kind of impact did this paper have on your career and the future course of your research?

DI: I gained more of an appreciation for experimental studies, and for the suitability of bumble bees and pollination as research topics. And the success of that work helped keep me going back to RMBL every year up to the present (and future!). The project on wildflower phenology that I helped initiate in 1973 and have continued to now was an outgrowth of my work with bumble bees, and the desire to learn more about the flowers they visit.

HS: Today, 39 years after it was published, would you say that the main conclusion still holds true, more-or-less: “resource use by a bumblebee species is influenced by the presence of other species and suggest that the phenomenon of competitive release can be observed in bumblebees. In this system, interspecific exploitative competition appears to be the primary mechanism involved in resource partitioning.”?

DI: Yes, I think that’s still a valid conclusion. There are some more sophisticated kinds of statistical analyses that reviewers and readers would look for now, compared to what I did back then.

HS: If you were to redo this study today, would you do anything differently?

DI: I probably would cast it in the context of a network of interacting species, as many community-level pollination studies are doing now. And as Berry Brosi (Emory University) has been doing with his recent work at RMBL, which included an experiment like mine. I’d probably also have some research assistants (as many graduate students do now) to help with data collection, and probably some other collaborators. And instead of using a mainframe computer word-processing program I’d use my laptop; my dissertation written in 1976 was the first one that was produced with a word processor in the Department of Biology at the University of North Carolina (I still have some of the boxes of 80-character punch cards on which it was typed). During my PhD research the first hand-held calculators became available, and one summer I was able to borrow one; it cost about $300 (my monthly salary at the time), and did only basic arithmetic. I’d have something more powerful now! Perhaps one advantage of that earlier work is that all the data were hand-written, and I still have the notebooks with those data from my dissertation, which I hope will facilitate someone repeating some of that work in the future.

HS: In the paper you say “I have never observed aggressive interactions between bumblebee species in the East River Valley.” Subsequent to the study, did you observe any aggressive interactions?

DI: No. I don’t think there are any reports of that kind of behaviour by bumble bees.

HS: You say “There is no obvious explanation for the different types of competition observed in bumblebees studied by Brian (1957) and Morse (1977) and those I studied”. Subsequent to this study, were you able to gain further insight into why the type of competition between bumblebees is different in different locations?

DI: Not really. In some of the communities they studied (in Europe for Brian, New England for Morse) there seem to be more interacting species, which must be partitioning resources in ways in addition to the differences in proboscis (tongue) length and altitudinal distributions that I concentrated on in Colorado.

HS: Have you ever read this paper after it was published? If yes, in what context?

DI: I’ve gone back to it only a few times, although I still watch those same bee species and wildflowers every summer, even in the same spot where I did that work.

HS: Would you count this paper as a favourite, among all the papers you have written?

DI: One of my favourites, as it was my first publication in Ecology, and I think a significant contribution to studies of resource partitioning and bumble bees.

HS: What would you say to a student who is about to read this paper today? What should he or she take away from this paper written 16 years ago? Would you add any caveats?

DI: Note that it’s possible to do experimental studies with bees and wildflowers, and gain insights that couldn’t otherwise be obtained. And that you can do this work with a minimum of equipment, and even by yourself. Think about the possibility of repeating studies of this vintage, as a way of learning about what effects climate change is having.

0 Comments