In a paper published in Science in 1998, Daniel Pauly, Villy Christensen, Johanne Dalsgaard, Rainer Froese and Francisco Torres Jr., using the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s (FAO’s) global fisheries catch data, showed that the mean trophic level had declined over the period of 1950 to 1994. In other words, fisheries, over this period, was moving from catching larger fish at the top of the food chain to smaller fish at lower levels of the food chain. Pauly and colleagues called this phenomenon “fishing down the food web”, and over the last 20+ years have continued to study the changes in fisheries and marine biodiversity across the world. Twenty-two years after the paper was published, I spoke to Daniel Pauly about his motivation to carry out the analysis presented in this paper, his memories of the time when this work was done, the paper’s reception in academia and the popular press, and what we have learnt since about fishing down food webs.

Citation: Pauly, D., Christensen, V., Dalsgaard, J., Froese, R., & Torres, F. (1998). Fishing down marine food webs. Science, 279(5352), 860-863.

Date of interview: 27 February & 17 March (via Skype)

Hari Sridhar: What motivated you to do this piece of work at this point in time in your career?

Daniel Pauly: We had written a well-received paper in 1995 – my first paper in Nature – which highlighted the importance of trophic levels for structuring the marine food web [1]. The concept of trophic levels had been controversial earlier because people had initially perceived them as integers – that they had to be integers – 1, 2, 3. And it’s only with W.E. Odum’s description of fractional trophic levels that they began to make sense. And because the transfer of energy – let’s call it energy – from one trophic level to the other is very low – only about 10% passes from one trophic level to the other – it is very important that this transfer be estimated properly. This was the basis of the 1995 paper. I was thinking about trophic levels, I gave Ms. Johanne Dalsgaard, a Danish student that I had as I began working at UBC, the job to look at the mean trophic level of the fisheries in the North-eastern Atlantic, that is around Western Europe. I don’t remember why I gave her this topic, but this was probably to explore the various aspects of trophic levels. She did a very nice term paper, and it showed a steady decline of the mean trophic level of the catch over four or five decades. I gave the paper a high mark.

At the time, I worked at UBC in Vancouver seven months of the year, and five months in my old job in the Philippines. So in the summer, a month or two later, I was eating lunch with my friends in Manila, talking about things, and I mentioned this paper. At the table were, I think, Rainer Froese and Villy Christensen, two colleagues with whom I’ve worked extensively. Suddenly, it hit me that we could do the same analysis worldwide and that it would mean something. We went back to our office and immediately set up to analyse the data. I had a research assistant whose name was Francisco Torres Jr. – Junjun was his nickname– and I gave him the job of extracting as many trophic levels that we had from FishBase and Ecopath food web models – and he assembled 200 of these estimates. It was important that we had lots of estimates because we wanted to prevent aliasing. If you average between two trophic levels, you get it wrong, especially if they are far apart; your analysis should be as granular as possible. Junjun did that and Rainer then assembled the FAO data. We computed mean trophic levels by year and region and wrote the paper [2]. It was really quick; in the paper, we had a big ecosystem model that explained how the trophic levels were obtained. But Science didn’t want that model. It’s funny because one reviewer said we don’t really want the theoretical explanation, but the data are nice. The paper was immediately endorsed by the reviewers.

At the time, we didn’t know about the need to have an outreach program parallel to that of Science, but the paper was picked up very widely by the press. A friend of mine, Andy Bakun, an oceanographer, happened to work at FAO and he mentioned that there were people – his colleagues at FAO – running up and down the floor saying there is an opportunity for them to have a paper in Science about why ‘fishing down’ was wrong and why they disagreed. Andy didn’t want to criticize our paper because he thought it was okay. So, John Caddy and a few others wrote this weird paper in which they conceded that this decline in trophic level might occur but mentioned four reasons we shouldn’t have seen it [3]. Now, the funny thing is that we had seen it; and, if their reasons why we shouldn’t have were correct, then the effect should be even stronger! In effect, this was a judo argument in which your opponent’s criticisms strengthen your position. The four contention points that Caddy et al. wrote about became a research program for us. For example, they said you should not be able to detect fishing down because the FAO data are miserable. They wrote that about their own data! When I wrote in other contexts that the FAO data have problems, they criticized us, but at the time they conceded that their data were too aggregated for us to infer anything. This was simple to refute. We constructed a well-disaggregated data set and gradually worsened its taxonomic resolution by aggregating the data it contained. This showed that when you group the data on species catch, into a catch by genus, nothing really happens; and neither from genera to families. However, when you move from families to orders, there is no resolution left in the data, and you lose the signal. This meant that if a decline in mean trophic levels could be detected despite the catch data being over-aggregated, the decline would be stronger with well-disaggregated data. What we did is what I later called ‘unmasking a masking effect.’

Caddy et al. also mentioned that we should not have assumed that the catch reflects the biomass left in the sea. That was true before when artisanal fisheries, for example, in India, did not modify much the biomass of fish available in the sea. But nowadays, trawlers catch everything in the path of their nets. So, obviously, if a country had only a few artisanal fisheries, there was no fishing down. But nowadays, since we exploit everything, there is fishing down. Later, incidentally, we were able to demonstrate – not in response to that paper, but to others – that, actually, the mean trophic level of the biomass declines faster than the catch. We recently published a paper about biomass decline in the Bohai Sea in China [4] based on what we call the ‘skipper effect’ because the skippers will try to get as many large high-trophic level fish as possible. Unfortunately, the biomass in the sea doesn’t include many of them anymore.

Getting back to Caddy et al., they also suggested that the abundance of small fish depends a lot on primary production of the sea and therefore, there would be large fluctuations. If you suddenly have lots of sardines, this would suggest a decline in mean trophic level – because sardines have a low trophic level -without the big fish having declined. We dealt with this argument by showing that the decline takes place even if we remove the lower trophic level. This was demonstrated remarkably well years later by Ms. Brajgeet Bhathal, an Indian student I had at the time, who demonstrated that in all Indian states and Union Territories fishing down occurs, particularly when you remove the Indian oil sardine, which is very abundant and fluctuates very strongly [5].

The fourth argument of Caddy et al. mentioned that as fishing proceeds, the fish gets smaller; a view also easily shown be a judo argument because if fish get smaller, their trophic level also goes down. This was demonstrated in a paper in the Canadian Journal of Fisheries with the help of a little model which incorporated available estimates of fishing mortality. However, it showed that the additional effect of accounting for within-species reduction of size was not very strong [6]. Overall, the Caddy et al. paper was a huge help because it was a reasonable series of arguments and because they helped us clarify things. In later papers, I described how they provided us with a research program in which we addressed each of these masking factors, one after the other.

Unfortunately, I discovered only later we had not addressed a strong masking factor. And that was expansion; the expansion toward offshore. In the Bhathal paper, there was an indication that, in India, the fishing along the coast proceeded until the 1970s.Then trawlers were given massive government subsidies to fish offshore, and they began to go offshore. In a sense, when you fish inshore and then move offshore, you’re exploiting another ecosystem. Since you’re going to encounter many previously unexploited fish offshore, the mean trophic level of the catch will increase. Now you have a situation where the trophic level goes down inshore, and you catch fewer fish and they have low trophic level, and you decide that some of your boats have to go offshore, so you can catch big fish again. This will result in an increase of the combined trophic level from both inshore and offshore. So, you have this effect which makes mean trophic levels go up. I had seen this, but I never thought that anybody would want to write about it, because when you talk about an ecosystem, what happens in the adjacent ecosystem shouldn’t be considered. It is, for example, as if you try to evaluate the effect of fertilizer on the productivity of two farms. The farms in both treatments must remain the same size. You cannot say, oh, yeah, the effect of the fertiliser was to increase my yield and besides, I have increased the size of the farm. This is so crazy. You have to compare the yield in farms of the same size.

But, in 2010, or a bit before, Trevor Branch from the University of Washington wrote asking me for the catch data from Sea Around Us, the research project I lead here at UBC. We distributed data on the catch of the world since 1950 that we had assembled using the distribution of the fish and the fishing fleets. Our policy is to share our data, including all the catch maps. I asked Branch what he wanted to do. He told me he wanted to check our data for the fishing down effect. I was pleased with that, but I told him to be careful, though, because as fisheries go offshore, the biasing effect mentioned above will occur. At the time, our catch maps didn’t show that because we were distributing the catch evenly over the whole distribution range of the caught fish. So, if it was a small catch, it was a small catch distributed over the whole area; and if it was a big catch, it was likewise distributed over the whole area. Now, we do it differently. When you have a small catch, it is usually distributed only inshore, because you catch fish only inshore. Only when the fishery becomes big, do you go offshore. So, I told him to make sure that, whatever he analysed, to consider the displacement of fisheries, like the farms getting bigger.

There was no response from Branch, and then a paper appeared in Nature which stated that fishing down doesn’t occur in reality. And when it seems to occur, it’s part of a cycle going up and down. I was outraged, but I realized that I was totally unprepared for that kind of attack. Because the points made were so absolute, I didn’t know how to answer. I usually can deal with journalists very well, but here I was totally flabbergasted. Among other things, I worked a lot on the Gulf of Thailand and a long time in Southeast Asia. In Thailand, as in India, there was a phase when small artisanal fishers were catching small fish and invertebrates close to the shore – sardine, anchovies, mussels and so on – that have low trophic levels. Then, the trawlers came in and the trophic level went up. Later, when trawlers’ catches totally dominated and the inshore fishery played no role, the trophic levels went down. So, to me, fishing down is the process that begins only from the time that you can catch everything with the trawls. It is the result of catching everything. A journalist told me that by not considering the earlier period, I had eliminated half of the data. But it’s was not the same thing! This earlier fishery was not an industrial fishery! But, at that point, I had lost, because it looked like special pleading. It is trying to make exceptions. I completely lost the argument, and I was also angry as hell.

For a few weeks or a month, the arguments in the press and social media were dominated by this notion that it is was all not true, that this was indeed all a figment of my imagination. Branch had gotten people as co-authors, I guess as before in the case of John Caddy, who used this opportunity to make a point in a paper in Nature. So, there was an ecosystem modeller, for example, who wrote that, based on simulations, you could very well have an ecosystem reduced in size, but which would contain as many trophic levels as before. The problem is that this goes against all of ecology. When you reduce the size of an ecosystem, it cannot contain large organisms. On land, if you have small patches of forest you cannot have tigers. Similarly, if you have a small marine reserve with intense fishing around it, you cannot have tiger sharks. But it was like I had been mugged by lots of people ganging up on me, armed with absurd arguments.

I was only able to write a little paper about adjusting one’s microscope; if you don’t want to see something, all you need to do is not adjust your microscope. I described the historic debate 200 years ago about whether the bodies of animals and plants were composed of cells or not, which could have been continued forever by people who refuse to adjust their microscope [7]. Fishing down is similar: if you don’t want to see it, you won’t. Thus, Branch keeps saying that the paper in which we uncover masking factors were all manipulated; basically, we create a downward trend, by eliminating one group or the other. For example, in India, he cites the non-consideration of the tuna in the Bhathal paper as if it was fraudulent. But in India, coastal ecosystems don’t include tuna, or only marginally. Tuna belong to oceanic ecosystems and the ups and downs of their population are not determined by factors occurring along the Indian coast. So, basically, I can justify the non-consideration of tuna in Indian coastal fisheries. But if you are arguing in bad faith, you can make a list of exceptions and it looks like we are manipulating the data. In fact, the fishing down paper was, in retrospect, excellent.

In the meantime, more papers have been written about these issues. We decided to address the expansion problem seriously. In the Bhathal paper, we had identified a way to present the expansion, but we could not combine it in one single expression with fishing down. We had a Fishing-In-Balance (FiB) index that showed the expansion, and we had a trophic level going down, but I didn’t know how to combine the two. My math was not good enough; I knew that we had to consider these two things simultaneously, but I didn’t know how to. But I had a postdoc at the time, Kristin Kleisner, whose husband, Hasan Mansour, was an engineer from Lebanon and very good at math. I talked about it with them, they took the challenge, and they licked the problem. Basically, it amounts to the following: you fish in a certain area, and suddenly the catch increases, and the trophic level increases as well. When you go down a biomass pyramid, you can catch more, but the trophic levels must go down. If the trophic level goes up when you catch more, it must be because you have gone offshore where you catch higher trophic level fish and lots of them.

The divergence between whether, as you catch more, the trophic level goes up or down, and when you catch less, the trophic level goes down or up, was used in an algorithm in R to separate the offshore and inshore catch. Kristin, her husband and I wrote a paper about this approach which we applied to lots of places and it worked [8]. Then, I got a Chinese PhD student, Cui ‘Elsa’ Liang, working with fisheries data from China. Elsa was not very comfortable with R, so she re-programmed the software as an Excel spreadsheet. She applied this to the East China Sea and could neatly separate the coastal areas from the offshore areas, and their distinct trophic level trends [9]. Thus, the when and how of the movement to offshore fishing is very well documented in China. Basically, the problem is now solved. This method was then built into our website, which currently identifies fishing down for all countries.

Colleagues have independently worked since on this in the Persian Gulf using Elsa’s spreadsheet, and they could show the offshore movement of the Iranian fleets. The fleets, in the 1950s, were all operating coastally, and they maintained a high catch by going offshore, further and further [10]. Thus, they confirmed the Liang and Pauly paper, which contrasted the taxonomic aggregation effect, which is very small, taking account of the size of the fish, and the offshore movement effect. And the offshore movement effect is the strongest of them all. Unfortunately, this is the one to which we didn’t give any attention in the beginning.

In retrospect, when I look at the 1998 paper, it was almost a miracle that it worked, at least for 50% of the regions, because the masking effect was very strong. And that’s the reason why, in 1998, I didn’t write that this is ubiquitous; that it occurs everywhere. But now I would; now I would say, as soon as you can take everything, there is a subtle or not so subtle changes in the composition of the fish community, with the bigger fish disappearing. For the 20th anniversary of this paper, I was going to write a massive paper on that, with lots of co-authors. But I have other commitments and it didn’t work. I will, probably, aim for 25 years! I’m old now – I was born in 1946 – but I will do it. Basically, there are two papers to write. One of them is a point by point refutation of the Branch et al. paper. This paper will not be published in the primary literature. It will be a report, where, paragraph by paragraph, the faults will have to be pointed out. And the second one will be a major paper, hopefully in Science or Nature or some other outlet, where we justify the claim that fishing down actually occurs everywhere; a claim we didn’t make in 1998. Also, I have edited an in-house report, in which two Brazilian colleagues have done – totally unsolicited, totally independently – a scientometric analysis of the reception of fishing down [11]. They could not have published this in the primary literature because it has no real hook; no non-intuitive results. However, they analysed hundreds of thousands of articles and classified them. Their most important result was their count of ‘pro’ vs. ‘contra’ articles: 80% pro and 20% contra. They used only the more restrictive Web of Science for citations, whereas the citations in Google Scholar are well over 5000.

HS: Could you give a rough timeline for this paper, starting with when you asked your student to do the term paper?

DP: It was in 1997, in the winter semester. So that would have been from January to early April. I returned to the Philippines in April 1997, where I talked about it with my friends. The paper was written in the summer; when I returned to Vancouver, and in early September it was submitted. The student, Johanne Dalsgaard, who did the little term paper, was also invited as a co-author. The work was done in the Philippines in the office of FishBase because we had people working there. We had a group led by Rainer Froese and a group working on Ecopath, on modelling, led by Villy Christensen. And my formal position at the time was Scientific Advisor to ICLARM.

HS: Apart from your student, were all the other authors in Manila when this paper was being written?

DP: Yeah, they were.

HS: Was the whole thing done during one visit to Manila?

DP: Yeah, because, at the time, we were producing, every year, a CD-ROM –a FishBase CD-ROM – and on that CD-ROM, Rainer Froese had put FAO catches, mainly because these FAO data were difficult to access; and they still are. Rainer had made them easily accessible by putting them on a CD-ROM because in Africa and elsewhere, they still have problems with connectivity, and by putting the FAO data on CD-ROM, people could work with them. Also, the FAO data could be matched against the valid fish names in FishBase. If you looked at the fish species on the FishBase CD-ROM, you could click on the name of a fish, and the catch of that fish would appear and so on. It was easy because Rainer has done all the work with the CD-ROM. We also wrote about fishing down in the FishBase book that one can consult online. We were, at the same time, writing what eventually became the 2000 FishBase Book [12].

HS: It also appears as a chapter in Five Easy Pieces.

DP: Yes, but that was 10 years later. What happened is, I went on sabbatical, the first time in my life. I spent three months in France, in Sète, where I wrote Five Easy Pieces [13], and three months in Bremerhaven, Germany, where I wrote Gasping Fish and Panting Squids, my book about oxygen and fish growth, now in its second edition[14].

HS: I wanted to ask you about two other people you acknowledge in the paper – A. Laborte and H. Valtýsson.

DP: Alice Laborte was a programmer at ICLARM in the Philippines. Hreiđar Þór Valtýsson was, at the time, a student at UBC; we called him ‘Radar’. He was from Iceland and later invited me to Iceland to a conference, and our paper at that conference was also about fishing down [15]. We demonstrated a very strong fishing down effect in Iceland. The Icelanders care about cod, and they maintain the cod, but everything else went down. Hđeidar is now a professor of fisheries at the University of Akureyri, in the north of Iceland. He was very much interested in the history of fishing in his country. When we did the catch reconstruction for the different countries of the world, he did it for Iceland. He had a long time series of catches and it was easy to do this fishing down demonstration for Iceland.

HS: What was Alice Laborte’s contribution?

DP: She was a programmer, but I don’t remember the details of what she did. It must have been programming the multiplication of the catch by the different species’ trophic levels. She worked with Rainer, not directly with me. I’m not good with data manipulation. I drafted the text, but I parcelled out the computational jobs. That’s what you can do as a Principal Investigator.

HS: A few years before this paper, you wrote the other paper that you are well-known for, the short note in TREE about shifting baselines. Was writing that short note, in any sense, a motivation for the work presented in this paper?

DP: I can respond, but let me first mention a nice back-story to that paper. One of the first emails I got – because sending and receiving emails was just beginning in1995 – was from the now late Lord Robert May. He was then a member of the Advisory Board of Trends in Ecology and Evolution, i.e., TREE, and as such, he was helping to complete an issue of TREE; the person who was supposed to write a column – called PostScript – had not done it. I could have written anything! This shifting baseline stuff was in the air, and I wrote it in a few hours and I sent it [16]. It was supposed to be page filler! This is a true story.

I’m interested in the humanities and history, particularly the history of science. The fact that fisheries science and ecology want to present themselves as ahistorical has always struck me as completely bonkers, because, of course, there is contingency. The notion that you have this perfect reversibility is silly because of the historicity of biological phenomena. Much is repeatable, but much is also not repeatable. And so, yes, I was always conscious of the fact that history shapes fisheries. I was always critical of computer jockeys working with only 20 years of data and ignoring earlier data because the files don’t have the proper format! It’s that bad in fisheries. People don’t use the data from the 1950s,1960s, or 1970s because they feel they are not reliable. But they are often more reliable than contemporary data because there were no quotas at the time, so fishers had fewer reasons to cheat about the size of their catch. Also, governments spent money to hire people who sampled fisheries data at a dockside. For example, in India, fisheries data were much better before than they are now. There was a vigorous sampling program that has been destroyed in recent years. To go back to your question, yes, there is a link between the two papers.

I also read absurd things. For example, the Branch group wrote that what determines fishing is profitability – which is true – and since shrimps are much more valuable than fish, fishers always went after shrimps, which have a low trophic level. But it is ahistorical because the big fisheries in the North Atlantic targeted ‘round fish’, cod, haddock, and other relatively large demersal species. And the English did not know about shrimp in the 1950s and 1960s. Many Americans didn’t know about shrimp either, and didn’t eat shrimp at that time. It is something that started in the 1980s, when people began eating sushi and seafood inspired from Japanese cuisine. Historically, the big fisheries in the North Atlantic were fish fisheries, and the shrimp were insects that you didn’t bother with. I’ve heard a British scientist reporting that the English skippers were throwing away shrimp because they were bugs. Eating shrimp and other insect-like marine animals is an acquired taste. And that’s a point of shifting baselines. Projecting the present onto some past without knowing that the past was different leads to errors. People often criticize me for things that they would know if they were looking at old books.

HS: Did you come up with the phrase “shifting baseline”?

DP: Yeah. But I recently discovered that, in the same month in the same year, social scientists working in the US published a paper about kids in Houston, Texas, that had never known a non-polluted air – non-polluted anything – and assumed this to be the normal state [17]. These authors called it “collective amnesia.” So, in fairness, one should say that shifting baseline and collective amnesia were published around the same time. However, in the natural sciences, the shifting baseline paper has had much more influence. It is cited well over 2000 times now. And it is credited with having launched the discipline or sub-discipline of historical marine ecology, which has its newsletter, called Oceans Past. Historical marine ecology is now a vibrant area of marine research combining history with marine biology and fisheries. The shifting baseline paper is one of its founding documents. Another founding document is the monster paper by Jeremy Jackson and colleagues demonstrating that marine over-exploitation began much earlier and had a much more significant impact than we assumed [18].

HS: Do you remember how you came up with the phrase?

DP: No. It was in the air. English is not my first language, but I’m always aware of the need for a nice turn of phrase. The first big deal that I did was a software to analyse length-frequency distributions of tropical fish which I called ELEFAN [19]. I attribute to the name ELEFAN a part of its success because, you know, people remember. If I’d called it TR15A, like a computer geek might do, that would have worked against its use. And, in fact, there was, at the time, roughly similar software; while they had at least the same goal, they had absurd names and they’ve faded away. So, I give lots of attention to the words I use to describe a phenomenon because this is part of the success that it may have.

HS: I want to talk a little more about the motivation for the ‘fishing down’ paper. Do you remember exactly when and how that idea came about, you know, to replicate this at a global scale?

DP: It was during a lunch meal with my colleagues at a little restaurant called Singapura, probably in May or even April 1997. The reason for wanting to globalize things is because I had realized a few years before that, in fisheries, we tend not to think globally. ICLARM was supposed to extend, to the marine realm in tropical countries, the lessons learnt from the Green Revolution. ICLARM became part of the Consultative Group for International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), the driving force of the Green Revolution. ICLARM was founded by the Rockefeller Foundation and was hovering at the edge of the CGIAR – they have these big centres – but we were not yet a member. But I knew of them. For example, I knew of IRRI, the International Rice Research Institute, in the Philippines. It is a very big institution. Lots of Indian scientists work there, and translate what they learned at IRRI into the Indian context, and everybody else does that for their own countries. IRRI scientists are aware of rice in the whole world. It has a database of seeds from all over the world and statistics for the whole world. But it was not only IRRI that had global statistics; FAO does, the Americans do, and so they can speculate on markets and predict yields on a global basis.

I realized that, except for studies by the FAO, we didn’t have global analyses of anything in fisheries. We began thinking about this in the early 1990s, that, yes, nobody but the FAO does global analysis and has global data. And this eventually led to my project, the Sea Around Us, that deals with fisheries statistics, but which had to be global if it was to be of any use.

There is another thing. I’m interested in science, in general, and the philosophy of science in particular. The great scientists whom we admire have discovered things that are valid universally. Physicists, for example, they know things that are being applying to stars other than our sun, and galaxies other than the Milky Way. One of my heroes, Charles Darwin, found a mechanism for evolution that would apply to life on another planet. This knowledge is not locale-specific. Every scientist we find in our textbooks has found something that has general validity. This is not description. If you only deal with local phenomena and you cannot generalize, you are in the business of describing. You’re not in the business of explaining. Explaining something is, in effect, mapping it to something more general. Fishing down was the second paper in which I tried to generalize something widely. At first, however, we reported fishing down as applying to many places, but we didn’t claim that fishing down was global because there were all the masking factors. Now I think this is a global phenomenon, but it is hidden in some places by masking factors. So, in this transition in my work, I wanted fisheries to also join various disciplines that make global claims. I’d read papers by people at Stanford, by Peter Vitousek, Paul Ehrlich, Harold Mooney and others, who had written about botany, about plants and primary productivity on a global basis. I think we should find globally applicable things and use them as defaults. Then, the local stuff that we study becomes a variation on a theme, or an exception, which will have specific reasons. This perspective is contrary to what is done now, where most colleagues work inductively. They are still stuck describing isolated things that they hope will be generalized. But if you don’t make an effort to generalize the things you study, who will do it?

We know from the philosophy and the history of science that the knowledge we have about the world should not only deal with things that we can do, but also about things that we can’t do. A scientific discipline that has a solid foundation has not only things that it knows, but things it knows cannot happen. However, for many colleagues, the sky’s the limit. They will describe anything. So, often, when they have a finding, it doesn’t confirm anything, it doesn’t disconfirm anything, it’s just there. That’s not how science should be done in terms of connecting one’s result with other scientists’ results. This is stamp collecting.

So, generalizing a local phenomenon from Europe or the Northeast Atlantic or Indonesia to the whole world was a logical step. I had discovered that there is a world out there with agencies that work globally and commodities to work on globally. My understanding of science is that it should be general and not specific.

HS: What do you remember about the peer-review and publication of this paper? Was it smooth? Was Science the first place you submitted this to?

DP: Very smooth. Unfortunately, I have not kept the review, but I remember one thing that a reviewer had written: “The interpretations may be naive, but the data are interesting.”That’s what I remember. One important feature of the paper is that we had estimated the transfer efficiency between trophic levels. We had provided an Ecopath food web model, a very complex one, as one of the figures. I remember we had to take it out because it was, I guess, overloading the story. And another thing that I remember occurred to my daughter Angela, who was, at the time, attending the International School in Manila. When the paper came out, the New York Times ran a story about it, but my name was misprinted as David Pauly. My daughter’s geography teacher, who was a very good teacher, asked the class to write an essay about that article. She smiled about it, and she later told the teacher that it was her father. So, yes, it was smooth sailing. But we did have to delete one figure. That’s all. I don’t remember anything else.

HS: Was Science your first choice?

DP: I don’t remember how we chose between Science and Nature. Perhaps, we had published in Nature before. I don’t remember how the choice was made.

HS: Tell us a little more about the reception of the paper. Did it attract a lot of attention as soon as it was published?

DP: Yeah. I have written about it in Five Easy Pieces.

HS: Let me ask you a more specific question. Many papers get attention from the popular press, but one thing that stands out about your work is how it manages to reach the people making decisions. Is that something that you consciously tried to develop right from the beginning?

DP: Yes. After several years working in developing countries, I understood the context of the science we did. We do science, and then managers are supposed to pick it up and use it. It doesn’t work that way. Fishery science and decision-making are not connected. In the mid-1990s, I began to move toward the conservation movement, toward the environmental NGO community, because I had realized that nothing is ever done in fisheries based only on science. To a large extent, the science is esoteric stuff. For example, Canada, which was supposed to have the best fisheries research establishment in the world – very good journals and very good studies – had lost an immense stock of fish in 1992 – the stock of Northern cod- because of overfishing. They closed the fishery, and a whole province went bust, with 40,000 people losing their jobs from one day to the next. This was a massive failure.

You can ask yourself, how the heck could it happen? It was obvious that it was happening, but politics could not really respond to the science. In the 1990s, I began to realize that this process was happening. Then, when I came to Canada in 1994, the first winter I spent here – because for four or five years I was commuting between Canada and the Philippines – I realized that Canada was doing precisely the same thing that I was noticing in developing countries. There was no good connection between the science and the management of fisheries. None. And that’s when I turned to the NGO community because the NGO community has leverage. It can reach politicians in a way that the scientists working for the government cannot.

And so, at a conference of the American Fisheries Society in Tampa, Florida in August 1995, representatives of NGO community such as WWF, Audubon Society were present; Carl Safina was also there with other NGO representatives. I went to them. They were huddled in the corner, not interacting with other people. I told them, look, I’m a fisheries scientist; I want to work with you. I was like a Martian to them, because usually fishery scientists only work with or for governments. To the NGO community, scientists are supposed to sign petitions and open letters to ministers and stuff like that. I said, I want to work with you, but not like that. I want to help you with doing analyses on which you can base your campaigns. They would have to be based on broad patterns that, in each country, take different forms. But you can count on the broad pattern applying throughout. And that argument worked. I’ve done work that WWF has used to reform of European fisheries and are used by various NGOs as background material on which to rest their tactical positions. I cannot be involved in the tactics that each of these organizations has, but I can provide them with strategic data.

For example, when people write that the world catch is declining, they have that data from us. FAO doesn’t admit that the world catch is declining, but we can show it. The research papers provide the conceptual infrastructure from which the various NGOs can work. That’s one reason why I’m getting all these citations. Now, I’m on the board of one of the biggest ocean NGOs, called Oceana, and we are funded by various philanthropic foundations in the US and Europe. So, the strategy of becoming the data provider for the NGO community has kind of worked. In1998, I was in the middle of this transition.

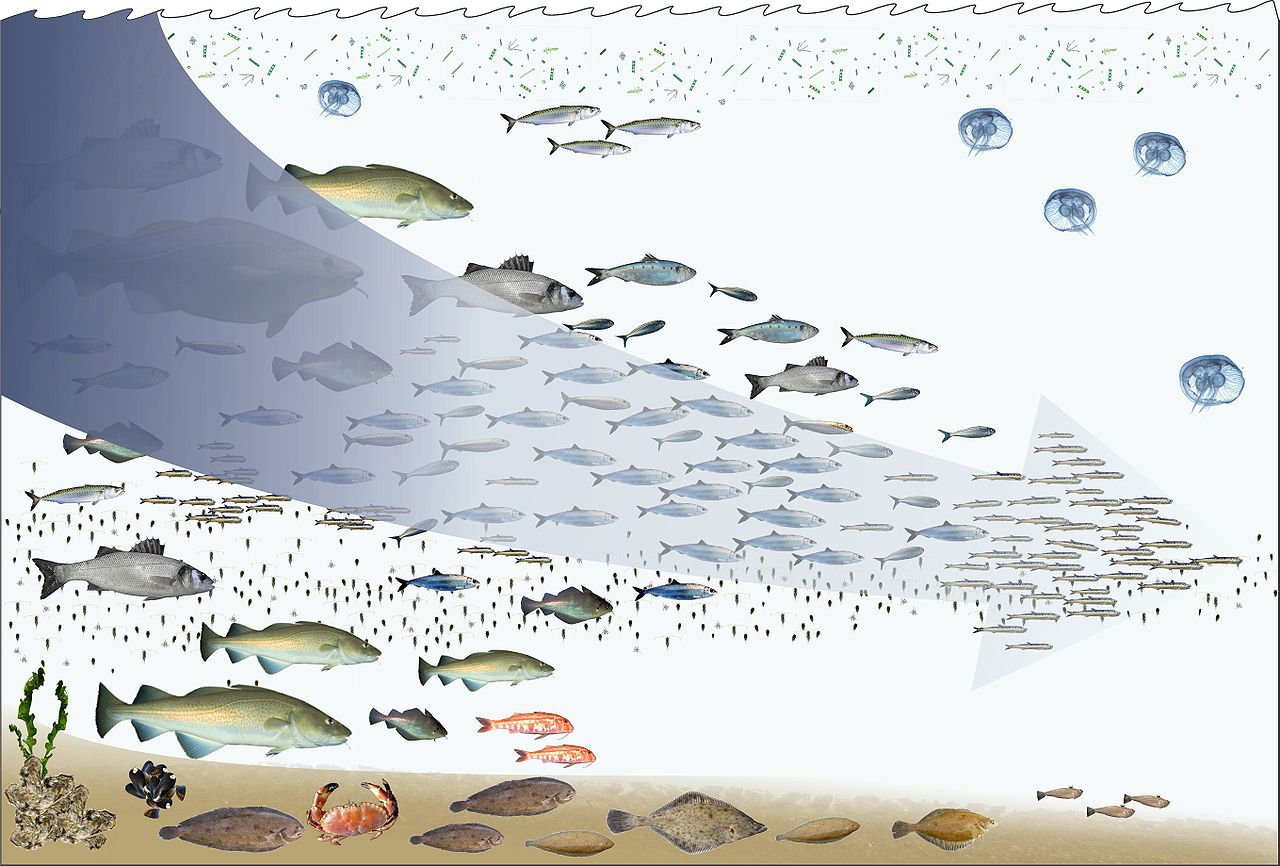

HS: Tell us about the iconic illustration linked to this paper, which you see so many versions of everywhere, but which was not in the original paper.

DP: FishBase, in the Philippines, employs an artist Rachel ‘Aque’ Atanacio, a young woman– well, she is not so young anymore – who processes the images of the fish we get for use in FishBase. She also makes graphs and other displays. I went to her and said that we would like to illustrate fishing down. There should be big fishes in the upper left corner and small fishes in the lower left corner, and I suggested what kind of fish they should be. At the bottom they should be some animals that look like flowers and they should become scarcer from left to right. She did that and she added an arrow- I forgot that she is the one who did it, but she told David Grémillet, my biographer. That was a good idea. But I’d forgotten that it was her, and thought it was me. Memory works like that – it is dangerous. This image now exists in various versions, but it didn’t exist at the time the paper was published, nor was it in the press release. It should have been; it would have been good. It was created a little bit later. I think it has become one of the most reproduced images in fisheries science; you find it in books all over the place. Its caption often contains: Conception – Daniel Pauly; Artist – Rachel Atanacio.

HS: What was your motivation to make this figure?

DP: Well, we had proposed a concept, and the concept needed a graphical representation. It’s one of those things that you think upon waking up in the morning: oh, my gosh, we should have that. Then you make it, and you have it.

HS: What has been the shape of the trend in mean trophic level of global fisheries subsequent to the paper, over the last 20+ years?

DP: The Caddy et al. paper from FAO said that, well – it’s difficult to see what it says, because they mention masking factors, but didn’t realize these masking factors would have the effect of strengthening our argument. Again, I believe that these authors were mainly concerned in having a little paper in Science. I mentioned that their paper provided the framework for us to write more about it. In 2004, the Convention on Biological Diversity included the Mean Trophic Index (MTI) as one indicator for biodiversity [20]. That happened because, when I was in Montreal, I was interacting with a staffer of the CBD who thought the MTI was neat and therefore put it on the agenda of a meeting they had in Malaysia. Since then, it continues to be an indicator that CBD recommends. That was a big deal, in a sense. And in our website, you can see that the page that presents fishing down also has the CBD logo.

The biggest challenge is the Branch et al. paper. Because it was a paper in Nature, it led to an avalanche of interviews. But I was not on top of it. Their paper came as a surprise. And all I could say to the journalist was that it was not right. I would have had to explain to journalists the thing about fisheries expansion. Journalists are not stupid, but they’re always pressed for time and because they have to quickly file their stories, they ask ‘yes or no’ questions. And if you have things to say that require a five-minute explanation, they will not be with you. It became a ‘he says, she says’ situation, for example, where you have been accused of doing something indecent, and you can only say you didn’t do it. I was completely like a deer in the headlights. I couldn’t do anything because I did not expect this to happen. If I had known, I would have prepared a website that I now have [21]. I really was disappointed with the colleagues who participated in the paper because they didn’t know what they were talking about. For example – we talked about this earlier – there was a well-known ecosystem modeller from Australia whose assessment of what can happen as an ecosystem gets smaller was that you can maintain all the trophic levels, which is simply wrong. Each paragraph of that paper can be challenged, and along with other authors that have published cases of fishing down, I can show that this phenomenon exists.

Philosophically, if you don’t want to see that something exists, it’s very easy: you just don’t look. Whereas if you want to show that it exists, you must, as I wrote, adjust your microscope. Branch has written lots of papers criticizing other people’s work, but few where he contributes new insights. He was lucky in being able to publish this in Nature. And, in his paper, there are lots of drawings of trendlines showing no decline of mean trophic levels in countries like Mauritania, where articles have been published by competent scientists showing declines in mean trophic [22]. So, basically, that paper is a giant fraud, but it is something that seemed to be okay because, if you ignore this expansion thing and you don’t correct for it, it looks like mean trophic levels go up and down more of less randomly.

I realized that I had not specified under which conditions fishing down would occur. I had not specified that if you trace the fisheries development of a country, like Thailand, for example, or India, you will start with the artisanal fisheries that catch little things, and then, as you industrialize, mean trophic levels go up. Then, when the industrial fishery is dominant, it brings everything down. But this ascen – the fact that mean trophic levels first increase, then decrease because of fishing down, then seem to increase again because of expansion – includes three different segments, which is two segments too many. I had not specified this in the earlier papers, because it seemed obvious to me that subsistence fisheries or small-scale artisanal fisheries would not be included. These fisheries didn’t fish down the Gulf of Thailand resources; you must have industrial fishing to do that. But because I had not specified this. I had exposed myself to this kind of thing. It’s like when you leave your kids in the house, and you tell them, we are going shopping, don’t do anything– don’t open the window, don’t do this, don’t do that – but you forget to tell them not to eat the flowers. And, therefore, they eat the flowers, because you have forgotten to tell them not to do that. It’s an obvious thing that you don’t eat the flowers, but you forgot to say that explicitly. But try telling that to a journalist who has to file in three minutes. I don’t blame them; in part, this is, my fault, and, in part, it is unavoidable. Some people are always watching you, because they know that if they can plant a harpoon on your back, they have caught a big fish. I ended up as the purveyor of a dogma, and Branch appeared to be the dashing hero who overcomes the dogma.

T. Branch, R. Hilborn, and a graduate student did a citation analysis of five papers they thought they had refuted, as if they were the gods of refutation. They had written that this paper is wrong because of X, and that paper is wrong because of Y. Then they showed the trajectory of the citations the year after they refuted the papers. They concluded that some papers had gotten fewer citations after their refutation, but the citations keep increasing for fishing down. Indeed, neither the so-called refutation by Caddy et al. in 2008 nor that by Branch et al. in 2010 has had any effect whatsoever. Citations are now above 5000 in Google Scholar. These people think that they are the judge, and if they should publish something, others should follow their view. They do not consider the possibility that every positive citation the paper gets is a refutation of their refutation. And, in a sense, that is what the citation analysis paper I mentioned earlier, written by Brazilian colleagues, shows, with their assessments that 80% of the citations are positive.

HS: I was struck by something you said in the paper, i.e., “zooplankton is not going to be reaching our dinner plates in the foreseeable future.” What is your thinking about that today?

DP: There is a whole story with the plankton. There was huge press excitement about the statement that I made, I think, in the press release:“We’re going to end up eating jellyfish because that’s all is going to be left.” And some of the drawings that Rachel did, had jellyfish at the end of the fishing down arrow. The jellyfish quote really captured the imagination of people. There were lots of articles about how we’re going to eat jellyfish. An amusing side aspect of this jellyfish thing is that the jellyfish scientists, a small group of perhaps 100 – 200 people in the world who work exclusively on jellyfish, ended up getting lots of interviews about jellyfish as food. I’m not joking. It was so strong – the interest of the public in jellyfish as food – because it was widely unknown that jellyfish were food. I even got officially invited to a jellyfish symposium to give a keynote. I didn’t go because, at the time, I thought this must have been a misunderstanding. I didn’t know anything about jellyfish, so I would not go and expose myself. I just used it as a catch phrase. But then, I got an invitation to the next meeting of jellyfish people, and I went. I was a keynote speaker in the second World Jellyfish Symposium in Brisbane. And I was invited to a third, in Argentina, also as a keynote speaker, because, in the meantime, I had put one of my students to work on jellyfish, and he found that, indeed, jellyfish were increasing throughout the world [23]. This opened another can of worms because many of the jellyfish people did not accept his result. So, basically, the fishing down paper shone a light on jellyfish. Even before this paper was published, Lucas Brotz, the fellow who got his Master’s and PhD on that, got a major article in The Economist, which published a map of jellyfish increases. When you have a student, he or she will acquire skills from you, but also all your enemies. Luca was thrown into such a situation. He found that there are more jellyfish, even after taking all kinds of precautions to make sure the pattern was not because there are more people on the beach that notice the jellyfish. But they still argued that there was no more jellyfish, that it was a delusion, and also that it is a cyclical thing. In the meantime, he has become a jellyfish expert. I have also published a few papers about jellyfish [24]. So, the jellification of the ocean was something we opened up. Also, the Norwegians are fishing for copepods in the North Atlantic and for krill in the Southern Ocean. They’re scraping the bottom of the barrel of marine life.

HS: So, we have, in fact, started putting zooplankton on our dinner plates.

DP: Yeah. It is happening now. The Norwegians are now fishing for zooplankton. They call it red feed, I think because the salmon’s flesh becomes red when they eat that stuff. The growth of this farming industry requires lots of feed. The plankton is one thing. The krill in Antarctica is the other thing, and myctophids – lanternfish – the other. They have opened a research topic in a leading journal of fisheries called ICES Journal of Marine Science. The editor is in Norway and he responds to what’s happening around him, and in Norway, they are interested in fishing myctophids and other mesopelagic fishes. These fishes, like plankton, are the base of the food web in the open ocean. So basically, the Norwegians, and industrial fishing in general, are now scraping the bottom of the food webs. The big fish are largely gone. That’s why I say fishing down is now ubiquitous. It’s now the thing that happens everywhere. It’s also the case in China, where all the wild fish have been reduced to minuscule sizes, and which are used in aquaculture to feed bigger fish. It’s called biomass fishing or bulk fishing. That’s what lurks at the end of the arrow. And the only way to reverse that arrow is to set up large marine protected areas. Because, if you do that, you get the big fish coming back. Actually, it’s not a bad idea, I’ve never shown the process with a reverse arrow, but we could do that.

HS: In the last para of the paper you say that “Globally, trophic levels of fisheries landings appear to have declined in recent decades at a rate of about 0.1 per decade, without the landings themselves increasing substantially. It is likely that continuation of present trends will lead to widespread fisheries collapses and to more backward bending curves, whether or not they are due to a relaxation of top-down control. Therefore, we consider estimations of global potentials based on extrapolation of present trends, or explicitly incorporating ‘fishing down the food web’ strategies to be highly questionable. Also, we suggest that, in the next decades, fisheries management will have to emphasize the rebuilding of fish populations embedded within functional food webs within large no-take marine protected areas.” Could you reflect on these lines, and say a little about to what extent what you proposed has happened?

DP: The diagnosis was 100 % correct. At the time people were thinking, oh, if we fish down and down, we can always catch more. It is not so. If you go down all the way, you lose the regulating role of the upper trophic level, and you find that the food web is no longer productive. You then have what we call a ‘backward bending curve’: you don’t find more at the bottom of the food web. The alternative to continuing to fish down and down is to rebuild. Rebuilding has become a big issue. It has become the big thing in the US and Europe, and it has become the big thing in Oceana’s program for the different countries where we work. Rebuilding is the thing to do everywhere. Large marine protected areas are needed as well. The Pew Charitable Trusts had, for the last 12 to15 years, a programme to create large marine protected areas in which the ecosystem can reconstitute itself. The whole discussion about marine protected areas is precisely about that. And so, I think that my prediction was validated. This is unlike the prediction I made in another Science paper [25] that fisheries would cease to expand because of increasing fuel cost. This was a wrong prediction, and a lesson in how not to predict things….

People are aware of the need to rebuild – that’s what they talk about -and rebuilding is achieved by fishing individual stocks less, and in several countries, this is mandated. The US and the European Parliament have passed similar legislation, but in Europe, they have problems implementing it. Canada has passed a similar law about rebuilding, but they don’t implement it as much as they could and they should. Large marine protected areas work, and now people realize we have to create as many as possible. And that’s why people talk about making 20-30% of the world ocean free of fishing. So, this prediction, I think, has the pulse of the time; this is what is happening now. People in fisheries are talking about rebuilding everywhere. We have to rebuild. Nobody talks about strategies to fish down the food web, and the countries that do it deliberately- China, Thailand, and a few others – are perceived as doing the wrong thing. In fact, they can do it only because they have aquaculture operations to eat the garbage fish they produce, because humans cannot eat them.

HS: Have you ever read the paper after it was published?

DP: Well, when I wrote Five Easy Pieces, I went back to it. I’d forgotten the ending of the paper.

HS: Did you go back to it when these papers criticizing the ideas came out?

DP: No, because various things that I have said have become part of me. When I talk about rebuilding, I talk about it using current issues; I don’t talk about it using the 1998 paper. But it’s the same thing.

HS: In an email, I’d asked you if this is your favourite paper, to which you said no and that your paper is one you wrote in 1984. Tell us more about that.

DP: Fishing down is something that is obvious and what might be called a first-order discovery. You plot the data and mean trophic levels go down. It’s not subtle, and it never would have caused a controversy! The oxygen story is subtle because you have to revise some concepts in your head that are totally in the way of understanding. I won’t invoke the word paradigm here, but it is something similar. Accepting fishing down is not a big deal. You see the big fish being fished, and the theory of fishing tells you that the fish gets smaller, at least within species. That big fish should disappear and small fish should replace them is trivially obvious. And so, I am happy about this paper, I didn’t botch it up – though I did botch up the response to the so-called 2010 refutation – but again, it’s not subtle. However, the oxygen story is actually subtle, and thus I have a big problem getting it across. The paper on primary production required to sustain global fisheries, for example, my first paper in Nature, is a little bit more complicated, but it’s also quite obvious. That’s why the title of my book was Five Easy Pieces. It was difficult to manipulate the huge amount of data needed and that’s why I had co-authors, because I’m not good with computers and numbers. Still, the concepts behind any of this stuff are obvious. Whereas, the oxygen story is deep [26]. You have to think differently.

HS: Looking back, what do you think have been your most important contributions?

DP: I think it will be fishing down and shifting baselines, then maybe FishBase. Then, if people look carefully, they will find that I was interested in the role of oxygen in fish growth, but they will not go into it, although I think it’s a bigger deal. I understand that it is frequent that scientists believe they got credit for something that they don’t consider their best work.

HS: How has this piece of work shaped your career?

DP: I would say, it’s like an author who writes all kind of books that he or she likes, and then one happens to become a best seller. Maybe like Rachel Carson. She wrote The Sea Around Us, which made her financially independent, and she was able to write Silent Spring. The Sea Around Us is a nice book, but Silent Spring is the book. I think that fishing down enabled me to acquire a certain stature. People can understand it easily, except for some problematic scientists who commit to the fishing industry. But again, it doesn’t require much to be able to assimilate the idea of fishing down. It’s one of these things about which one could say, why didn’t I think of it earlier? Thomas Huxley is supposed to have that said that about Darwin’s natural selection because, actually, in a few words, you can you can say what it is. Same thing with shifting baselines. You can summarize it in a sentence. The oxygen story is more difficult to summarize in one sentence, but it has far more implications. If you understand it, you’ll realize that much of the biology taught today has missed the point for animals that are breathing water. I am in a situation – like a rubber band – where some colleagues will agree as long as I am around, and then, when I turn around, they let go of the rubber band and go back to their original position. They cannot wrap their mind around what I’m saying. But I’m not too frustrated. This is the way it is.

HS: What would you say to a student who is about to read this paper today? Would you guide his or her reading in any way? Would you suggest any other papers they should read along with this? Would you add any caveats they should keep in mind when they’re reading this?

DP: Yeah, the caveat should be that there are lots of masking factors, and the small-scale fishery catches made before industrialization don’t count. Those would be the caveats. I would add that this paper embodies a lot of we know about biology, i.e., that big fish need longer to mature and reproduce. Therefore, they will be the first to go if you have a fishery capable of accessing them. In science, you want the hypotheses that you propose to encompass lots of data and explain lots of phenomena. You don’t want to explain details; you want to explain big things, ideally. And fishing down explains many things from food web theory, life-history, growth, mortality, and other aspects of biology.

HS: Would you suggest they read any other papers, either from your work or other work, that will be useful to read along with this?

DP: I would recommend they read Five Easy Pieces, because it puts the papers in context and shows a tremendous number of connections between the different pieces. They were not isolated silos, you know, resplendent in their isolation, but instead, they were steps. They were steps without much height between the first and second, the third and fourth, and the fifth paper. They were easy to ascend. The ‘easy’ in the title is real. Once you can see trophic levels as structuring elements, it all follows.

Literature cited

[1] Pauly, D. and V. Christensen. 1995. Primary production required to sustain global fisheries. Nature 374: 255-257.

[2]Pauly, D., V. Christensen, J. Dalsgaard, R. Froese and F.C. Torres. 1998. Fishing down marine food webs. Science 279: 860-863.

[3] Caddy, J.F., J. Csirke, S. M. Garcia, and R.J. Grainger. 1998b. How pervasive is “Fishing Down Marine Food Webs?” Science 282: 1383a.

[4] Liang, C and D. Pauly. 2019. Masking and unmasking fishing down effects: The Bohai Sea (China) as a case study. Ocean and Coastal Management https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2019.105033

[5] Bhathal, B. and D. Pauly. 2008. ‘Fishing down marine food webs’ and spatial expansion of coastal fisheries in India, 1950-2000. Fisheries Research 91: 26-34. doi 10.1016/j.fishres.2007.10.022.

[6] Pauly, D., M.L.D. Palomares, R. Froese, P. Sa-a, J. M. Vakily, D. Preikshot and S. Wallace. 2001. Fishing down Canadian aquatic food webs. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Science 58: 51-62. doi 10.1139/cjfas-58-1-51.

[7] Pauly, D. 2011. Focusing one’s microscope. The Science Chronicles. The Nature Conservancy, January 2011: 4-7.

[8] Kleisner, K., H. Mansour and D. Pauly. 2014. Region-based MTI: resolving geographic expansion in the Marine Trophic Index. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 512: 185-199.

[9] Liang, C. and D. Pauly. 2017. Fisheries Impacts on China’s Coastal Ecosystems: Unmasking a Pervasive ‘Fishing Down’ Effect. PLoS ONE 12(3): e0173296, doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0173296.

[10] Daliri, M., E. Kamrani, A. Salarpouri, and A. Ben-Hasan. 2021. The Geographical Expansion of Fisheries Conceals the Decline in the Mean Trophic Level of Iran’s Catch. Ocean & Coastal Management 199 (January): 105411.

[11] Santos,S.R.andM.Vianna.2020.Apreliminaryreviewofthereceptionof‘fishingdownmarinefoodwebs’, pp. 35-50. In: D. Paulyand V. Ruiz Leotaud (eds.) Marine and Freshwater Miscellanea II. Fisheries Centre Research Reports 28(2). Institute for the Oceans and Fisheries, University of British Columbia.

[12] Froese, R. and D. Pauly (Editors). 2000. FishBase 2000: Concepts, Design and Data Sources. ICLARM, Los Baños, Philippines, 346 p. [Distributed with 4 CD-ROMs; previous annual editions: 1996 – 1999. Also available in Portuguese (1997, transl. of the 1996 edition), French (1998, updated transl. of the 1997 edition by N. Bailly and M.L.D. Palomares) and Chinese (2003, transl. of the 2000 edition by Kwang-Tsao Shao, Taiwan); updates in www.fishbase.org).

[13] Pauly, D. 2010. Five Easy Pieces: How Fishing Impacts Marine Ecosystems. Island Press, Washington, D.C., xii + 193 p.

[14] Pauly, D. 2019. Gasping Fish and Panting Squids: Oxygen, Temperature and the Growth of Water-Breathing Animals – 2nd Edition. Excellence in Ecology (22), International Ecology Institute, Oldendorf/Luhe, Germany, 279 p.

[15] Valtysson, H.Þ. and D. Pauly. 2003. Fishing down the food web: an Icelandic case study. p. 12-24 In: E. Guðmundsson and H.Þ. Valtysson, (eds.) Competitiveness within the Global Fisheries. Proceedings of a Conference held in Akureyri, Iceland, on April 6-7th 2000. University of Akureyri, Iceland.

[16] Pauly, D. 1995. Anecdotes and the shifting baseline syndrome of fisheries. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 10(10): 430.

[17] Kahn, P.H., Friedman B. 1995. Environmental views and values of children in an inner‐city black community. Child Development 66:1403– 1417.

[18] Jackson, J.B.C., M.X. Kirby, W.H. Berger, K.A. Bjorndal, L. W. Botsford, B.J. Bourque, R.H. Bradbury, R. Cooke, J. Erlandson, J.A. Estes, T.P. Hughes, S. Kidwell, C.B. Lange, H.S. Lenihan, J.M. Pandolfi, C.H. Peterson, R.S. Steneck, M.J. Tegner and R.R. Warner. 2001. Historical overfishing and the recent collapse of coastal ecosystems. Science 293: 629-638.

[19] Pauly, D. and N. David. 1981. ELEFAN I, a BASIC program for the objective extraction of growth parameters from length-frequency data. Berichte der Deutschen wissenschaftlichen Kommission für Meeresforschung 28(4): 205-211.

[20] Vierros, M. and D. Pauly. 2004. Assessing biodiversity loss in the oceans: a collaborative effort between the Convention on Biological Diversity and the Sea Around Us Project. Sea Around Us Project Newsletter, May/June (23): 1-4.

[21] http://www.fishingdown.org/

[22] Meissa, B., and Gascuel, D. Overfishing of marine resources: some lessons from the assessment of demersal stocks off Mauritania. ICES Journal of Marine Science. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsu144

[23] Brotz, L, W.W.L. Cheung, K. Kleisner, E. Pakhomov and D. Pauly. 2012. Increasing jellyfish populations: trends in Large Marine Ecosystems. Hydrobiologia 690(1): 3-20

[24] Notably: Pauly, D., W. Graham, S. Libralato, L. Morissette and M.L.D. Palomares. 2009. Jellyfish in ecosystems, online databases and ecosystem models. Hydrobiologia616 (1): 67-85. doi 10.1007/s10750-008-9583-x; and, Palomares, M.L.D. and D. Pauly. 2009. The growth of jellyfishes. Hydrobiologia, 616: 11-21

[25] Pauly, D., J. Alder, E. Bennett, V. Christensen, P. Tyedmers and R. Watson. 2003. The future for fisheries. Science 302: 1359-1361. doi 10.1126/science.1088667.

[26] Pauly, D. 2021. The Gill-Oxygen Limitation Theory (GOLT) and its critics. Science Advances, 7: eabc6050.

0 Comments