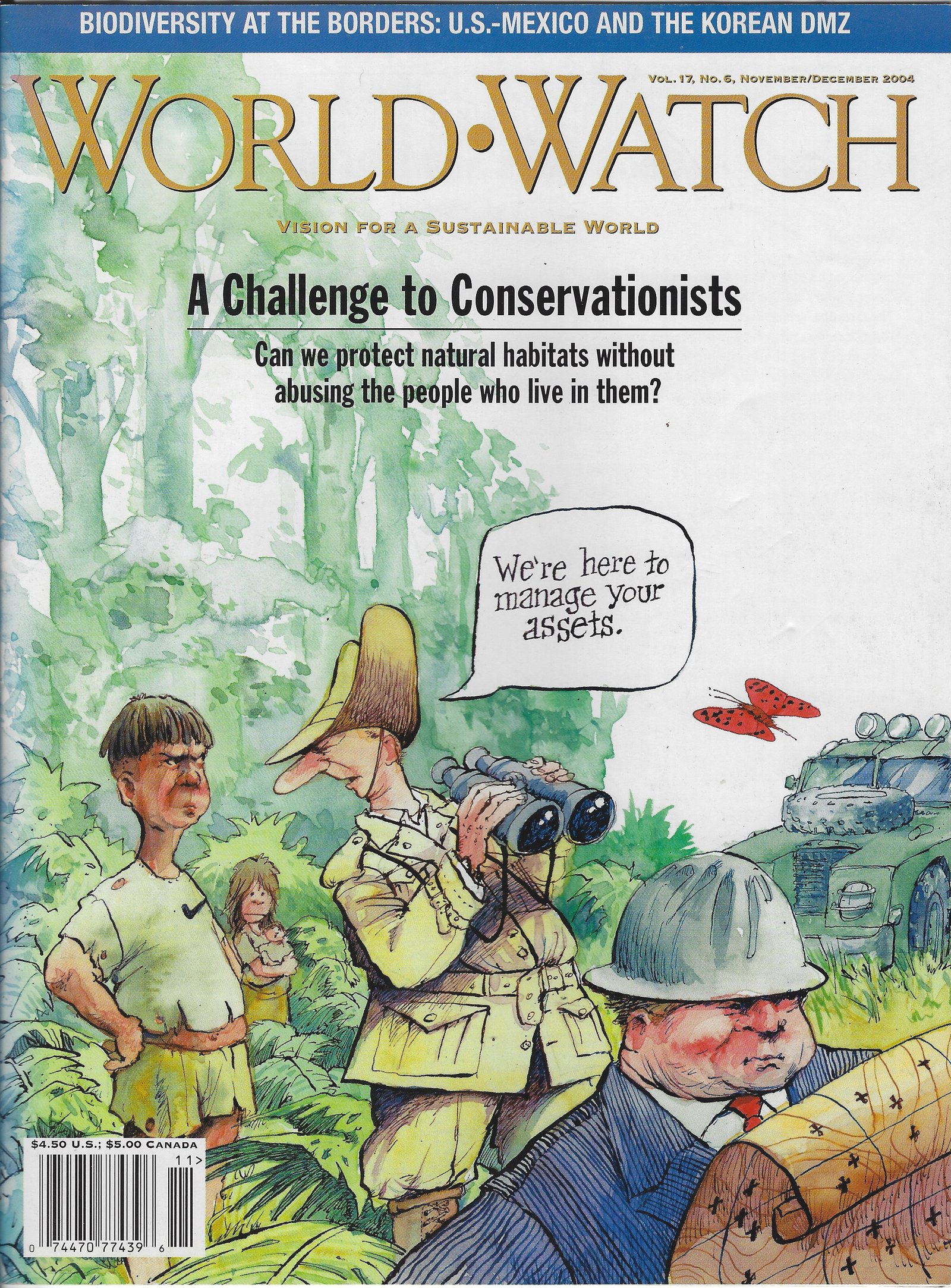

In an article published in World Watch magazine in 2004, Mac Chapin critiqued the work and style of functioning of three big conservation NGOS — World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Conservation International (CI), and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) — , especially in relation to their neglect of indigenous peoples living within their areas of work. Based on a variety of sources including published literature, conversations with NGO staff, and his own personal experiences, Chapin argued that the relationships of these NGOs with indigenous groups stems from conflicts of interest linked to their government and corporate funding. The article, as you will see below, created a storm, before and after it was published, and attracted, both, criticism and praise. Eighteen years after its publication, I asked Mac Chapin about his reasons for writing this article, the controversies surrounding its publication, and how he views the relationship between conservation NGOS and indigenous peoples today.

Citation: Chapin, M. 2004. A Challenge to Conservationists. World Watch Magazine, 17(6) November/December: 17–32.

Date of interview: This interview was conducted over a series of email exchanges between 2 March and 11 April 2022.

Hari Sridhar: What got you interested in the relationship between conservation and indigenous peoples, and motivated you to write this article?

Mac Chapin: I lived with the Guna Indians in Panama for three years in the late 1960s, with the Peace Corps. I became aware of the Guna’s close relationship with their natural ecosystems, and how they were threatened by colonization from non-Indians and “modernization” in general. That inspired me to study anthropology, and in the mid-1980s I started working throughout Central America with Cultural Survival, an indigenous rights NGO. From the start, we focused on indigenous rights and conservation; and in 1992 we collaborated with The National Geographic Society on a bilingual Spanish-English map of Central America showing the forests and indigenous regions of occupation and use. There was a clear correspondence, and we began working on programs that emphasized the two areas.

Some of the large conservation organizations (WWF & CI) expressed interest (TNC was not very interested) and we tried to work with them, but, unfortunately, collaboration was difficult, often impossible. They developed their programs without consulting with us or, more importantly, with the indigenous peoples living in the areas they wanted to conserve. They felt they knew more about conservation than the Indians, who were excluded from their programs; and beyond this, there was often hostility toward the peoples living in the areas they had singled out for their work.

This situation was coming to a head in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Indigenous peoples were getting organized in Central America and they began complaining — to us and to some of the private foundations that were funding the conservationists. Several of the foundations were meeting and discussing this at a gathering in California, and the Ford Foundation decided to hire an anthropologist who has worked in Mexico and an economist from India to do a study. I knew the anthropologist and we spoke, and he started feeding me material; he also got me in touch with the economist, and I started expanding my research. I had no thoughts of publishing what I was writing; I just wanted to clear things up in my head, and see how widespread the problem was (it was very widespread).

I was very close to Ed Ayres, the editor of World Watch Magazine. Ed is very principled and stands firm for things he believes in. He phoned up one morning when I was almost finished and asked what I was up to. I mentioned my research and sent a draft to him. He phoned the next morning and asked where I was going to publish it. I said I had no thoughts about it, and he said “Then, we’ll take it.” It was obviously an issue that was on many people’s minds at the time, yet nobody was writing about it.

HS: Stepping back a bit, can you trace the origins of your interest in indigenous communities’ rights? What led to you spending three years living with the Guna Indians, as part of the Peace Corps?

MC: When I was young, I read many books about travel to exotic (for me) parts of the globe: Africa, Latin America, the Near East; both fiction and non-fiction. This interest grew out of my very early reading of comic books: Tarzan, Scrooge McDuck (who was always heading off to distant lands with Donald and Huey, Dewey, and Louie), Tintin, and so forth. I graduated to tales of Richard F. Burton and the search for the origin of the Nile, the adventurers of hunters and animal collectors in Africa and the Amazon Basin, the British Empire, and on and on. This was my search for adventure, pure and simple. After my undergraduate studies (History of Medieval and early modern Europe) I began traveling myself, to Europe and Turkey and Israel… And in 1965 I joined the Peace Corps in the Dominican Republic, where I spent two years working with small-holder coffee farmers. In 1967 I rejoined the Peace Corps, this time with the Guna Indians in Panama, and stayed there for three years as director of an agricultural school. On the strength of all this practical experience, with Caribbean Blacks and Central American Indians, I decided to study anthropology. With my degree in hand, I set out to apply my knowledge helping the indigenous peoples of Central and South America to hold onto their lands, natural resources, and cultures.

You will see that I began vicariously with literature that can only be described as “colonialist” and ended up somewhere on the opposite end of the spectrum. The heroes of virtually everything I had been reading and thinking about were white males of European descent (except perhaps the Disney Ducks — but they sure acted like White males); and the “natives” in the colonized regions of the world were depicted as submissive and not terribly bright — often like children needing a helping hand from the civilized and powerful. But of course in this world things don’t work that way. The literature had a strong effect on me, and it took years to shed it, and only partially. At the same time, I strongly believe that the contrast between the two groups — rich and poor, 1st World vs. 3rd World — allowed me to understand the ramifications, the scarring impact of the power differential. This didn’t happen all at once, like a flash of lightning. It was gradual, and after many years in the field and thinking and writing about rural development, and seeing the power differential up close, I believe I understand, to some extent, what is going on. At the same time, I have to catch myself from time to time from practicing what I don’t preach. No matter what, I am a member of the class that runs the world, and I often feel like Lady Macbeth, who, try as she might, cannot clean her blood-stained hands. But I try.

In this context, the actions of the large conservationist organizations are a prime example of the ugly face of this imbalance.

HS: What motivated you to join the Peace Corps in 1965, and again in 1967?

MC: To be perfectly honest, there were two major considerations: (1) I saw it as an excellent opportunity to see places in the world, and learn a foreign language; and (2) I chose it as an alternative to going to the Vietnam war.

HS: The World Watch article draws upon different sources of information – relevant literature, conversations with NGO staff and others, your own personal understanding of the history and finances of these NGOS, etc. Could you tell us a little more about the research that went into the making of this article?

MC: This was a combination of things. I was working with indigenous people in Mexico, Central America, and South America, and had begun working in Africa and New Guinea. I was hearing the same things from people in all of these places, especially with regard to the large conservation organizations. Representatives from donor agencies, especially the small ones, had begun discussing the same issues. I knew many of them and they were concerned. I also knew people in the large organizations, and they were concerned. On a more personal level, our NGO (Native Lands) was in a constant struggle to raise funds for our work, and the conservation NGOs were siphoning off the money — ostensible for work with indigenous peoples, which was largely a sham. There was plenty of information about all of this, but nobody had brought it together and written about it. When the Ford Foundation hired the anthropologist and the economist to look into the matter, we shared some of the ideas we were working on, papers, reports, proposals, etc. In other words, it was a combination of sources, and they all formed a coherent pattern of abuse and neglect. The difference between my article and the Ford Foundation report was that I could say what I wanted (which was what people were saying) and the Ford consultants could not. Ford made sure they pulled some of their punches.

HS: What happened after Ed Ayres offered to publish the article in World Watch?

MC: In summary, a draft escaped, all of the conservationist NGOs got hold of it and they contacted World Watch, trying to have it squashed. The editor told me: “This is the first time the shit has hit the fan before an article has been published!” He weathered the storm nicely, but there was a fair amount of commotion surrounding the issue of the magazine. A woman who had a small foundation had offered to give World Watch $30,000 to cover the cost of destroying the 30,000 copies of the magazine that had already been printed and republish it with an altered (sanitized) version of my article. This was done without informing the editor or me. It was a crazy, half-baked scheme and was abandoned soon after, but it had already become public. The editor stood up for me and in the end the magazine was distributed with the article untouched. The woman in the small foundation was trapped: she had been pretending to be on my side, but this exposed her, and she resigned shortly after. The following issue of the magazine contained 16 pages of letters about the article, most of them positive.

I think the article had a powerful impact. It opened up a needed debate; it ignited a broad movement among many indigenous organizations worldwide; and the recent environmental congress in Glasgow, Scotland, apparently pledged to support indigenous peoples on conservation issues. On the other side, the big conservation organizations — WWF, TNC, CI — have been trying to co-opt the issues raised in the article for their own benefit, with what they say are initiatives to help indigenous peoples. But at least it is out in the open, and indigenous and tribal peoples are taking up the cudgel and fighting for their rights — something they were not involved with to any extent before.

HS: You conclude your article by saying:

What’s needed now is a series of independent, non-partisan, thorough, and fairly objective evaluations that answer key questions the NGOs can’t credibly answer. These evaluations should be undertaken by nonhierarchical teams representing the various sectors— indigenous peoples, local communities, national NGOs, government agencies, and donors, including bilateral and multilateral donors (whose influence is enormous) and private corporations (which have been largely silent)—and should be prosecuted in the spirit of seeking information and insights, not justifying existing programs. Together, these stakeholders need to pursue the kind of open, public discussion that can lead towards the creation of conservation programs that are responsive to the needs of both biological and human diversity worldwide.

Have such evaluations happened anywhere? In the 18 years since this article was published, have you seen any examples of conservation programs that you think are “responsive to the needs of both biological and human diversity”?

MC: I’m afraid I have dropped out of those networks almost entirely over the last 10 or even 15 years. So I cannot say what has happened. The above comments constitute a “wish list” that is certainly overly optimistic. Who would do such a study? There is a lot of money at stake: the large conservation NGOs want to look good so they can get money; the donor agencies want to look good, so they don’t want to look partisan; and indigenous peoples and local groups don’t have any power (or money), so they cannot afford to criticize anyone. And we end up with the same blockage. As they say in Spanish, another ride on the same donkey (“otra vuelta en el mismo burro”).

Just a couple of days ago [as on 22 Mar 2022], I was speaking with someone who continues working in this field and he said that in the recent gathering in Glasgow people were talking about the need to work with indigenous peoples on conservation initiatives, and they were talking about tens of millions of dollars. This sounds like a move in the right direction. But how in hades would this work? Who would handle it? Which indigenous groups would get the money, and for what? If those with the money and in charge of organizing the distribution of $$$ don’t do it “correctly” it will hurt indigenous peoples. It needs to be done carefully, sensitively, and responsibly — but I doubt that will happen. On the surface, it sounds like it will do more harm than good.

Please excuse my cynicism, but I have seen this sort of thing before, many times.

HS: Why do you think it might “do more harm than good”? What might the “right” approach look like?

MC: I’m afraid, based on experience, that the donors (who are varied; largely private foundation in the United States, and a mixture of government and private donors in Europe) will want to throw lots of money at the problem. If they give oodles of money directly to indigenous organizations, things could go awry fast. Few of them in Latin America, a region I know best, presently have the administrative capacity to manage money responsibly; they are learning, but they need help on this. The large conservationist NGOs see their role as working on conservation, not administration – or any of the other needs of indigenous organizations, such as land tenure and employment (“too political,” they often say). Also, we are in a transition phase, in which indigenous groups want to take more control of their own programs, and many are increasingly seeing non-indigenous NGOs that work with indigenous peoples as unnecessary, and their role is being questioned by both indigenous peoples and donor agencies. Into this mix we find the largest donors wanting to do something big and fast (after all, the problems facing all of us are quite large) and this will never happen if they are forced to fund small, less sophisticated indigenous organizations. So they stick with the large conservation NGOs. There are very few donor agencies that have experience with indigenous peoples, and too much money too fast can cause havoc. It can easily destroy the organizations they are attempting to help.

Much of this is predetermined. In the environmental programs of the large foundations the staff have invariably come directly from the large conservation NGOs, and they funnel their money directly back to their colleagues. This has always been the case with the largest private foundations — MacArthur, Moore, Packard, Hewlett, and Ford Foundations — and the same pattern is found throughout the donor community. The number of foundations with programs to work with indigenous peoples is miniscule. If donors want to really help indigenous peoples, they should provide support for institution strengthening, land rights, and employment generation – things indigenous organizations desperately need. These are the priorities of indigenous peoples. But they are not the priorities of the conservationists, and trying to jam conservation down the throats of indigenous and tribal peoples will go nowhere. Donors tend not to see this, and they are invariably unhappy with what indigenous peoples do with their money. This is repeated over and over and over…

HS: How has the increasing dependency of conservation organisations on corporate funding affected their relations with indigenous peoples?

MC: This has become a huge problem. It not only causes the conservation NGOs to ignore indigenous peoples; it has served to disfigure their mission and turn a blind eye to the unsustainable, destructive activities of the corporations; and, I might add, their relations with abusive governments, such as Brazil, where the Amazon rainforest is vanishing with astounding speed. Conservation NGOs can be thrown out of a number of countries for working with indigenous peoples on environmental issues (or any other issues, for that matter). Granted, the conservationist NGOs are caught in an impossible situation, but they are the ones to blame.

HS: The article includes the following note from the editor:

We anticipate that this article will launch an open and public discussion about a complex and contentious issue that has been debated behind closed doors in recent months. While the fresh air may at times be chilly, we believe that active, engaged discussion is essential to resolving these issues and to strengthening the conservation and indigenous community movements. The author of the article is an active “player” in that debate, and we look forward to publishing other views in the January/ February issue. We therefore invite all interested readers, including staff of the “Big Three” conservation organizations discussed herein, to submit responses for publication. We welcome the views of indigenous people, NGOs that are working with indigenous groups, foundations or agencies that fund such work, and others concerned with these issues.

Could you tell us about the response the article received at the time it was published, both formally and otherwise?

MC: The editor was quite right about this, and he got a strong response, especially from indigenous people and representatives of NGOs that work with indigenous peoples. Most of the reaction was positive. The three large conservationist NGOs sent in measured responses, admitting that they needed to do more to work with indigenous peoples in the field. Ford gave a defensive, not-terribly-honest response that missed the mark altogether. But the reaction on the whole was positive and constructive.

Most important, however, is that the article opened up discussion on the issue and it has continued to this day. Much of it now resides with indigenous people, who have become more openly active in the defense of their lands and conservation of their natural resources.

HS: Are there ways in which science (and scientists) can contribute to repairing this fraught relationship?

MC: It is my experience that the conservation NGOs use science to exclude indigenous people. They advertise themselves as doing “science-based conservation,” which sets them apart from indigenous people, who are not, in their eyes, “scientists.” (Here there is a disagreement regarding the meaning of the term “science.”) With the conclusion that they need to be guided by the “real scientists” (themselves). Does this sound familiar? My feeling is that biological science has much to contribute, and indigenous people could learn a good deal from it. But it has to be a two-way street, for the conservationists can learn a good deal from the indigenous people. Unfortunately, it all boils down to power and money, two things the indigenous people do not have.

HS: Do you have any suggestions on what biologists can do differently (e.g. in what they choose to study, the approaches they take, the interpretation of their data) to help repair this relationship between conservation and indigenous groups?

MC: What the biologists/conservationists need to do is stop imposing their agendas on indigenous peoples. They have to listen to indigenous agendas and take them seriously. They could do this by spending time with indigenous people and experiencing their lives, what their problems are and how they deal with them. What their thoughts are on a variety of issues such as natural resources, food, sustainability, economics, and land tenure. I know, this would take time, but something along these lines need to be done. Without it, there will be no meeting of the minds and no basis for negotiating terms, and collaboration. There will be no respect or trust on either side of the divide. The biggest obstacle at present is the imbalance of money and power, both of which are on the side of the conservationists. It allows them to push their own agendas, using the excuse that they know what is right for the planet. I don’t think we can change this. In other words, I am not optimistic.

HS: The president of World Watch, Chris Flavin, in his note accompanying the responses to the article, mentioned that they planned to convene a meeting in early 2005 to bring together key players in this issue “to consider concrete steps that will better mesh the needs of indigenous peoples and the natural world”. Did such a meeting happen? If yes, what came out of it?

MC: There was a meeting in Washington, D.C., but from what I heard about it, there was no resolution. The conservationists pledged to work more closely with indigenous and tribal people, but I never heard much about it beyond the meeting. Flavin did not organize it. I remember that the Aspen Foundation was in charge of the organization of the meeting. The Ford Foundation might have sponsored it. But again, I don’t think there was any follow-up.

HS: Earlier, you indicated that you didn’t continue to work on this issue much beyond this article and completely “dropped out of these networks” 10-15 years ago. If you don’t mind my asking, why was that?

MC: I did begin a project to look into relations between sympathetic NGOs and indigenous groups in Latin America in the years following the article. My aim was to understand the dynamic and make some recommendations. Over the next couple of years, I took several trips to Peru and Ecuador and contracted some anthropologists involved in this sort of work in Central America. And I came up with a lot of information and insights, and much of it was quite illuminating. What I found was a series of problems with NGOs working with indigenous peoples, and it would have gotten people in trouble if I had published it – and I would have gotten myself it trouble with some of my colleagues in the field. This is a terribly complex area that is full of snags, contradictions, and self-defeating policies and practices. NGOs, for example, have ties to donors and they don’t want to offend them and have their money cut off; they are often caught in the middle, between the donors and the indigenous people. The European NGOs get money from their governments and there are policies attached, all of which limits what they can say and do. A close friend advised me that if I published what I was coming up with I would lose all of my friends in the field. In short, it is a pretty grim picture; so I simply passed on a few notes to some of the NGOs and dropped the matter. My frustrations are summarized in a paper I never published. It was a blockage I was in no position to overcome. So in the end I dropped the matter and moved on to other things.

HS: Looking back, what is the place of this article (2004, World Watch) and the study on which it was based in the long arc of your career?

MC: I see the article as a small blip in my career path. I value much more the work of bringing indigenous peoples together in Central America and Mexico by helping — with various indigenous groups — to organize regional conferences and workshops dealing with natural resources, land tenure, and cultural identity; and also the mapping projects we set up with groups in Latin America, Africa, and New Guinea, and the mapping of Central America we did with National Geographic (1992 & 2002) and the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (2015). These maps were collaborations with the indigenous peoples and showed natural ecosystems, indigenous territories of occupation and use, and protected areas. All of this mapping, in which indigenous people and local villagers mapped their lands according to their wishes, have been extremely influential and have had a powerful impact at all levels.

The mapping we did with a number of indigenous peoples in Latin America, along with the work in Africa (Cameroon) and New Guinea (West Papua and Papua New Guinea) was a first step in which people in all of these areas have begun to learn about the practical value of mapping and learn to do the mapping themselves. They have begun to learn the technology of cartography; they have been working with professional cartographers in their own countries – and the cartographers have learned new skills to work with indigenous people in the field, with field data, for the first time (before this, they had only worked with aerial photographs – never field data). The mapping has been a real collaboration of people and technology, and the maps have been recognized as valid – “official” – by governments everywhere we have worked.

When I consider all that has been done with the organizing and especially the mapping, the World Watch article was a minor diversion.

HS: What might you say to a young conservationist who is about to read the 2004 article?

MC: Just be aware of the issues it raises. I can’t force anyone to behave as I would like. But they should know what the dynamic between conservation and indigenous rights is, and perhaps learn something that can lead to a more constructive partnership in the field.

This is very refreshing read, Hari.

Many congratulations and a big thanks to you for this coverage.

Looking forward to read your blogs again!

Vidya