In a paper published in the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society in 1983, AJT Johnsingh reported the findings of his study on large mammalian predators and prey in Bandipur Tiger Reserve, Karnataka. This study formed part of Johnsingh’s PhD dissertation on dholes, likely the first PhD in wildlife biology by an Indian biologist. In addition to providing valuable quantitative information on the abundance of mammal species and predator-prey interactions in Bandipur, the paper is remarkable also for its insights into the natural history of mammals, especially their predatory and anti-predatory behaviour, as well as for the photographic documentation of rarely seen behaviours in the wild. Thirty-nine years after the paper was published, I spoke to AJT Johnsingh about his motivation for carrying out this study, memories of fieldwork, and his thoughts today on the study’s findings and interpretations.

Citation: Johnsingh, A. J. T. (1983). Large mammalian prey–predators in Bandipur. Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society, 80: 1-57

Date and place of interview: 10 September 2022 at AJT Johnsingh’s residence in Bengaluru.

Hari Sridhar: I’d like to start by asking you about the motivation to do the work that is presented in this paper. In the Introduction, you say that the main motivation was to look at the impact of dhole on chital and that the study follows-up on the study by HC Sharatchandra and Madhav Gadgil [JBNHS 72: 625- 647. (1980)] that had suggested that chital are declining in number because of predation by dholes. But your paper contains a lot more than the dhole-chital interaction. Can you tell us a little more about the making of this study, including why you decided to do it in Bandipur?

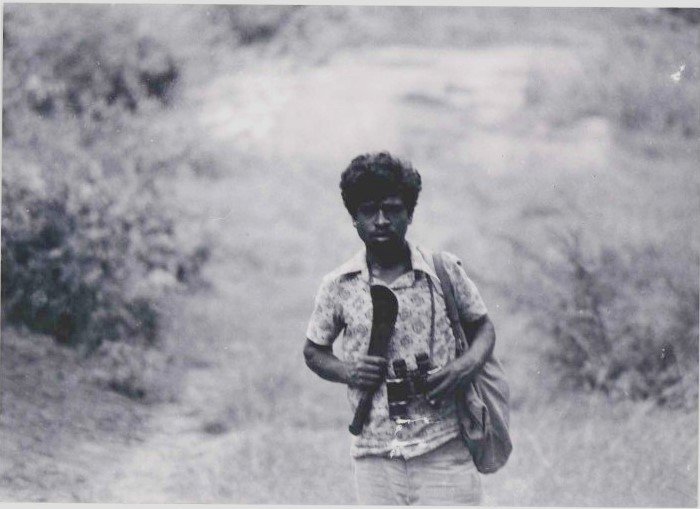

AJT Johnsingh: It all goes back to my meeting with JC Daniel. I think that was in May 1971 when my father, brothers, some friends and I were camping in Kalakkad hills. Daniel had come with Rom Whitaker; Daniel looking for lion-tailed macaques and Rom searching for king cobras. We met inside the forest accidentally. We were staying in Manjolai coffee estate on the way to Neterikal, which is abandoned today after it became part of Kalakad-Mundanthurai Tiger Reserve. Daniel asked me what I was doing, and I told him I was an MSc Zoology graduate from Madras Christian College and that I was teaching in Ayya Nadar Janaki Ammal (ANJA) college in Sivakasi. Daniel said, if you’re a zoology graduate, why don’t you make some observations on wildlife? I said, I don’t know anything about it; I’m not trained to do that. He gave me his card and asked me to be in touch with him. If any opportunity came up, he said he would let me know, so that I can start making some observations on wildlife. I was in regular touch with him after that. After some time, he wrote to me saying that one Michael Fox, an American professor, was coming to study dholes in Cheetal Walk, ERC Davidar‘s jungle home in Sigur Range near Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary. Daniel asked me if I was willing to go and work with him for three months. I said if my college gave me permission I would go. Daniel wrote to Madurai University, the university wrote to my college, and I got six months permission with lien on service but no salary. That was in January-March 1974 and in October-December 1975, my first exposure to real wildlife habitat, where there were elephants and sambar and chital and so on. Interestingly, during the six months in Cheetal Walk, in spite of my walking around a lot I never saw a tiger pugmark. That was soon after tiger hunting was banned, and according to Davidar, who, although a lawyer, was a good naturalist and hunter, tigers were poached out by the local people in the Sigur Range as there was no one to come and hunt the cattle lifters. At that time, there were lots of cattle camps in the Sigur Range. Now the cattle camps have been removed and there are tigers now.

After I did that work, Daniel suggested that I should do a PhD on dholes. He told me that Madhav Gadgil had a field station in Bandipur, where the habitat is fairly open, and so it might be an ideal site to study dholes. I said yes, and thanks to WWF-India [World Wide Fund for Nature-India], which arranged the funding for me. I first went and met late DG Wesley in Bandipur, who was the field director of the Reserve. He told me I could study dholes but that I shouldn’t walk in the Reserve. But I didn’t have a vehicle, so I had to walk. He then allowed me but with many restrictions – walk only on the eastern side of Bandipur-Mudumalai road, not on the western side! People like late Zafar Futehally and late MA Parthasarathy supported me a lot then and helped me to get permission from the forest department. That’s how I ended up in Bandipur studying dholes for my PhD.

As my supervisor, I had registered with one late Professor Krishnaswamy at Madurai Kamaraj University, who I think was a former classmate of Mr. Daniel. Krishnaswamy was a copepod specialist; he didn’t know anything about wildlife. So there was nobody to really guide me. Even Madhav Gadgil told me that there was no way I could study dholes as he and his team rarely saw them in Bandipur. He said that I should instead do some line transects and count pellets in the different vegetation types, which will give me some data for my PhD. In that paper you mentioned, Sharatchandra’s and Gadgil’s estimates for Bandipur were something like 800 chital, 20 sambar, a pack of 40 dholes, 10 tigers and large number of leopards etc. Such a low chital population will be eaten up by that many predators in one month! I had George Schaller‘s book “The Deer and the Tiger” with me, which I was using to try to learn the methods to do the study. There was nobody to give me the idea of what I should do.

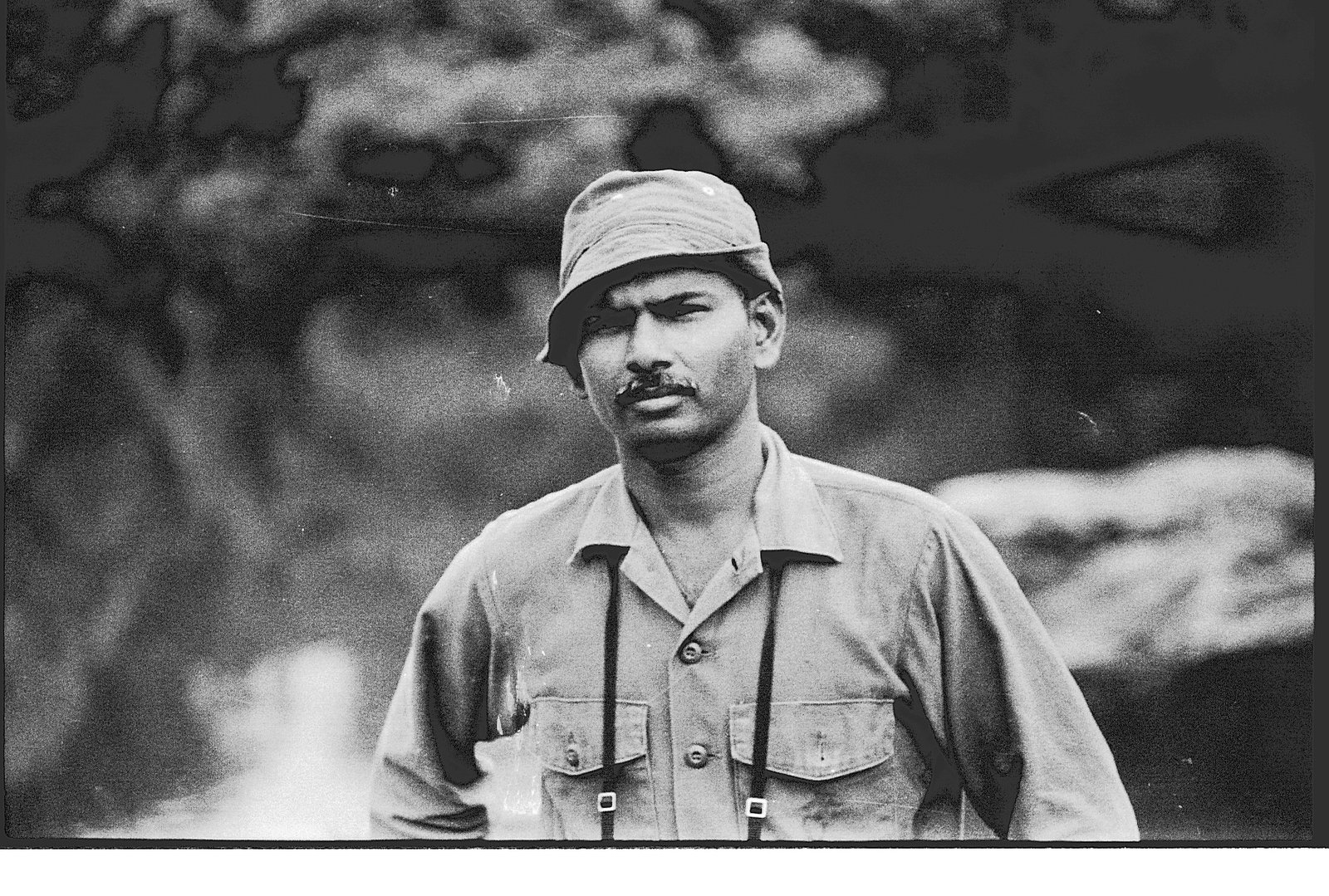

I decided I will count the chital and sambar in that area, collect kills, collect scats of dholes, and also of tiger and leopard because they also occur in that area. I hired two Kurubas as my assistants. In Sigur Range I had, with much fear , hesitation and prayer in my heart, developed the capability to walk alone in the jungle and this enabled me to often walk alone in Bandipur Tiger Reserve. Dholes prefer to hunt early morning or late in the evening. So, looking for dholes early morning, I would walk in one direction, and my assistants would go in another direction. Mid-day was spent looking for kills. If we had not succeeded in locating dholes in the morning we would continue the search in the evening. It was difficult to sex the dholes and identify individuals, yet I became familiar with one dhole which had a bent right pinna and so I called it ‘Bent Ear’ (the story about it can be read in “The Whistling Hunters”, in my book “On Jim Corbett’s Trail and Other Tales from Tree-tops“). As I was mostly working on foot, my area of operation was only around 30 sq.km. We collected the lower jaws from the kills for aging. My field assistants would come back in the evening and give me their information, and I’d record everything. The good thing about chital is that, in the months of June-August, after the rains, they form large aggregations, and so it becomes much easier to count them. Sometimes, I would go in the tourist vehicle and count them, because if I was in a vehicle the chital would not run away; I could get a fairly good idea about the chital numbers. Sambar don’t occur in such large groups, but, eventually, I became familiar with the places where sambar used to go and stay during the day, and would go there, flush and count them.

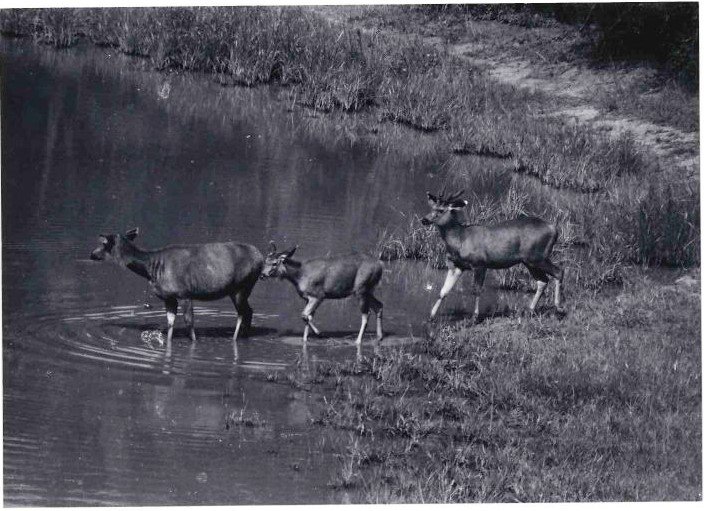

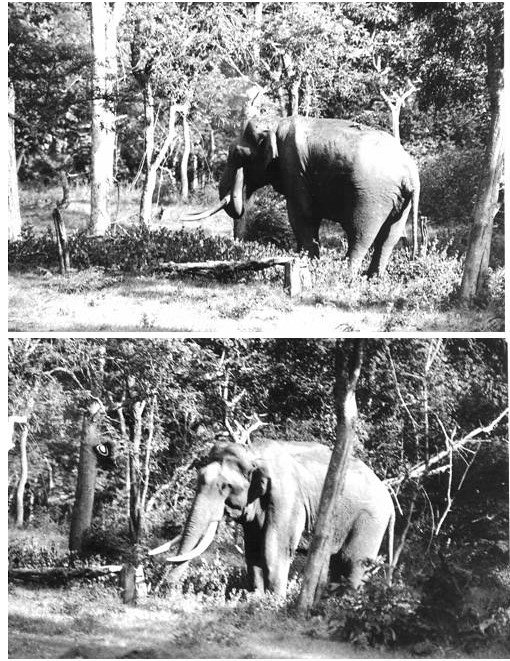

I have some amazing black and white pictures of sambar from that time because I knew exactly where sambar could be found. Once, late Professor Val Geist from Canada, came to study chital in Bandipur. He was invited by Madhav Gadgil. He stayed for a month and developed a great liking for me as he saw me walking in the elephant jungle. He was a great field man and a hunter. One day, he said, Johnsingh, I want to take some pictures of sambar, which for him was more like elk. So I took him to a pond called “Karigowdane Katte” about two kilometers west of Bandipur. I knew that sambar came to rest near that pond in a depression overgrown with Lantana, and which route they would take if we flushed them. I asked Val Geist to stand behind a Butea frondosa tree, and then I went and flushed four Sambar to run in front of him. When I asked him later if he got good pictures, he said, “yes, but if I had my bow-and-arrow I would have easily shot one!”

HS: Did the idea to walk line transects also come from Schaller’s book?

AJTJ: Schaller doesn’t talk about transects in that book. In some discussion, I must have learnt about line transects, but I did not convert that information properly into results. We had made eight transect lines, each four kilometers long, which we used to walk every month and record sightings. But nobody told me that it was important to record sighting angle and distance to calculate densities, so we only got some encounter rates from that data. I had even divided my study area systematically into grids. Late Rauf Ali, in those days, used to tell me, if you could plot your sightings of tiger, leopard, and prey and put everything together in the grids, it can be brought out as an excellent paper. But that never happened.

HS: In what ways did the experience you gained working with Michael Fox help in your PhD?

AJTJ: My work with him in the Sigur forests gave me the first-time opportunity and experience of working and walking in a wildlife-rich jungle. Honestly, I went there even without knowing the difference between a common langur and a bonnet macaque! Michael Fox was a behavioral scientist. He’s written books on the behavior of dogs and wolves, and so on. The work I did with him was basically collection of kills; not much of ecology. It did not help me very much in planning my study.

HS: I want to get a sense of the timeline. You said you met JC Daniel for the first time in May 1971. Do you remember when he told you about this opportunity with Michael Fox?

AJTJ: Soon after, because we started the work in the Sigur Range in January-March 1974. Then we again went for three months, October-December in 1975. The second time when Michael Fox came, he brought two Master’s students: James Cohen and Bruce Barnett.

HS: When did you start your field work for PhD?

AJTJ: In August 1976.

HS: You mentioned in another conversation that you had to take leave from your college.

AJTJ: College gave me three years leave with lien on service but no salary. For two years, my field study was supported by WWF. Madhav Gadgil’s idea was to compile everything – my information, Sharatchandra’s information, and also of one [S] Narendra Prasad who was studying bamboo – and write a book about that. He gave me support for 10 months. That’s how I sat and wrote my dissertation at Centre for Theoretical Studies in the Indian Institute of Science (IISc). [NV] Joshi used to help me with statistics.

HS: In the Acknowledgments, you mention that NV Joshi helped you with an analysis looking at the effect of predation on Chital and Sambar, and Madhav Gadgil helped you with inferring prey numbers from scats.

AJTJ: [Laughs] Later, Ullas [Karanth] told me, Johnsingh, what you did with the scat number to estimate the prey number was totally wrong. You should not have done it. I didn’t have the capability to understand that, but Ullas being good in quantitative ecology could see the problems with the way we had inferred prey numbers from scats.

HS: Can you talk a little more about the two assistants who worked with you? What were their names, and in what ways did they contribute to this study?

AJTJ: Very interesting. One of them was called Sivaji because he used to act like the famous Tamil cine-actor Sivaji Ganesan. I found him to be cheating. I’d ask him to go to one area, but then later when I went there he won’t be there, but would say he was there. So, I dismissed him. Then one Bomma joined. Kurubas are mortally afraid of many things. Bomma refused to climb some of the large, old trees. There was a huge Terminalia bellirica tree, on which I would ask Bomma to climb and sit, to record animals, but he would refuse because he believed the tree had ghosts. Once when I went home in Tirunelveli and came back to Bandipur, I was told Bomma had a high fever and died. Then I was joined by a very nice field assistant called Keechanna; very brave and very sincere. He used to walk barefoot and could climb any tree. He was a very great asset. You know, at that time, I used to tell the forest department: you’re pushing all the tribals out of the forests. Suppose tomorrow anybody wants to go to Bandipur to do a study, there will be no Keechanna there to help and guide them. Keechanna was quite short, so he’d tell me, sir, you’re tall and can easily locate elephants, so you go in the front, and I will come behind. Once we came across a tiger on a fresh Sambar kill. There were jungle crows swarming around and the tiger was growling and chasing them. This was at Siddarayan Katte, a pond about two kilometers from Bandipur towards Mudumalai. I told Keechanna, let me go closer, hiding, and take a picture. He told me firmly, sir, don’t do that. It could be very dangerous because if the tiger sees you approaching the kill it can be on you within seconds. That type of very good advice also he would give me.

HS: What about his knowledge of wildlife and in particular Wild dogs?

AJTJ: He was good in locating kills, which was very important for me. When you hear a lot of alarm calls or see jungle crows descending down in the forest you don’t rush and look for the kill. You need to climb a tree and check if there is a tiger or a leopard around. In fact I located all my tiger kills (19) and leopard kills (56) with the help of jungle crows. By the way, I had the record collection of dhole kills: 302. I think most of the jaws from those kills are in the Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc. That type of basic jungle craft Keechanna knew very well, which was very useful for me. These things are very important for your survival, especially in elephant country. I learnt a lot by working with Keechanna.

HS: One part of your study looked at how kill stealing by people might affect Dholes.

AJTJ: I had a feeling that one or two of the tribals were regularly going out to locate dholes and stealing their kills. They would have stolen tiger and leopard kills also, as they lived in the jungle, not far from Thavarakatte, then an area frequented by tigers. In the first two months of my work, I came to know about 10 to 20 kills, but I could get the jaws of only 2-3 animals; the rest were taken by these people. So I complained to the forest department and eventually they stopped it.

Once near Bandipur I went to the extent of beating a boy who came to steal the kill on which the dholes were feeding and I was observing. I chased him and beat him with a cane I was carrying and he got fever. His father was a very strong man and he said, if my son dies, Johnsingh better not walk alone in Bandipur. But at the same time they liked me also and I was kind to them in all possible ways. They used to say, you are one among us. You are walking like we walk in the jungle. So, despite that beating incident, I did not earn their enmity. These tribals were exceedingly poor, you know. They were paid so little and I had enormous sympathy for them.

Kill stealing was a problem but eventually it was stopped. Cattle grazing was also a problem. Lot of cattle used to come from Mangala village till Aralikatte near Bandipur-Mudumalai road. I told the forest department about it and they could stop it. Also, people from Bandipur used to go all the way to Aralikatte to cut firewood. I told the forest department to let them go to the north to cut, beyond my study area. That too the forest department could implement. In a way, therefore, when I was there, I was like a honorary wildlife warden and could give some protection to that area from grazing, firewood cutting and kill stealing.

HS: In the paper’s abstract, you say that the high predation rate you documented in Bandipur (predators removed nearly 20% of standing crop of hoofed prey) was “possibly because of the sudden removal of 100+ cattle from the study area which were grazing till the beginning of the study.”

AJTJ: Yes, Bandipur was declared as a Tiger Reserve in 1973 and I went there in 1976, when the forest department was in the process of removing cattle. Possibly in the first year of study, the existing cattle there (say 100+) were removed from the area, and I feel this resulted in higher predation by wild predators.

HS: Today, what is your view on “kill stealing”, in terms of the magnitude of its impact on the dhole population?

AJTJ: A small population of Kurubas living there and stealing kills won’t have much effect, actually. If it is widely prevalent throughout the reserve, then it can have an impact. You should read “Tiger Moon” by Fiona Sunquist. She and Mel Sunquist were our neighbours in Front Royal, Virginia when I went there to do a post-doc. Fiona is British and Mel is an American, so they occasionally used to quarrel about whose English is better – English English or American English! Anyway, in “Tiger Moon” she writes about stealing of kills by elephant mahouts in Chitwan, where Mel did his study on tigers. She says it is a big worry. Stealing kills was a big problem even in our country in those days. If you read EP Gee‘s book, “Wildlife in India“, he describes how, in one of the places he went to, early in the morning he saw people cutting meat.

HS: Did you read these books during your PhD?

AJTJ: No, no, afterwards. I came to know about Fiona Sunquist when I went to the Conservation Research Center, established by the Smithsonian Institution in Front Royal, USA after submitting my thesis. When I was teaching in the college in Sivakasi, there was no opportunity to read such things. I was teaching zoology, playing football and volleyball in the evenings and going to the nearby Rajapalayam-Srivilliputhur hills with my colleagues and students whenever we had free time.

HS: In the Introduction, you cite a number of other studies in the region, in Nepal and in Sri Lanka and so on. Did you come to know of those too after you completed your study?

AJTJ: When I was doing my fieldwork in Bandipur, I was staying at Madhav Gadgil’s field station. I started reading some of the literature that was available there. That was when I first came to know that if I’m going to write a thesis I need to read. This paper was written when I was in Front Royal. John Seidensticker told me that we should seek the help of Fiona for editing, for which we could pay her. Front Royal had a fantastic library. For writing this paper, I probably got most of my information from there.

HS: Two things are really striking about your work. One is something you’ve already alluded to, which is working on foot in an area that is dangerous in different ways – elephants, tigers, bears…

AJTJ: Also, cobras and vipers. It had a good population of cobras and vipers. That’s why I always carried a cane which I had brought from Upper Nilgiris. I had gone there with late John Joseph, who was then the Warden of Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, when he was looking for some poachers; he had jurisdiction over the Nilgiris too. I used to go into the forest wearing chappals because that made it easy to quickly climb trees. Whenever I needed to climb a tree, I could quickly remove my chappals and climb. So I needed to be extra careful about not stepping on any dangerous snakes.

HS: Where did this courage come from? Was it because you’d already had a lot of experience being out in the wild growing up?

AJTJ: Once you start understanding, you get the courage. First of all, you have to understand the elephant is not looking for you as prey. Tigers are shy of people, but sloth bear, the most dangerous animal in our forests, needs to be avoided. Dholes, even when they are on a fresh kill, don’t attack, even when you go to remove the lower jaw of the kill. Once, a range officer told me that dholes will attack if any one runs in front of them. One day I saw nine dholes on the road. I ran in front of them towards a climbable tree and they all ran in the opposite direction! Even when I approached an active den with young pups the mother/guard dhole would run away. Michael Fox used to tell James Cohen, who was terribly afraid of elephants, that the pachyderm is not a carnivore; elephants are not looking for you to prey on you. I tell everyone that, in elephant areas, you should see the elephant before it sees you, hear the elephant before it hears you. Elephants make good amount of sound while feeding and when they sense you they give a “druuuuudruuuu” sound to warn you. On a hot day, elephants resting in the shade will keep flapping their large ears and even that sound “dub…lub. dub…lub” can be heard from a distance if you’re silent and alert. Wind direction is very important. If the sun is behind you and the wind is from the direction of the elephant, you can approach fairly close, silently, using some cover. If you follow these basic things you reduce the risk a lot. Fortunately, I never encountered a group of elephants on my path while returning to my camp in Bandipur late in the evening; solitary elephants, one can quietly avoid them and go. But I have still been very badly chased by elephants a few times. And after I witnessed that incident where [NR] Nair, an IFS officer, was charged by an elephant from a distance of 70 meters and killed, it made me more nervous. I have written about this in detail in “Field Days“. So, I was never walking comfortably in the elephant country, as I would walk in a park. I used to walk in fear, and carefully. The only “weapon” I carried was a small knife to remove the lower jaw from prey that was killed by predators.

HS: The other aspects that stands out about this paper, and more broadly your approach to research, is the emphasis on careful natural history observation. How did this come about?

AJTJ: Here I will give a lot of credit to Jim Corbett books. Reading Corbett’s books really made me appreciate natural history and help me develop my jungle craft.

HS: What do you feel about the state of natural history today? In your opinion, how has the knowledge and appreciation of natural History among field biologists changed over time?

AJTJ: The amount of walking I did, or the amount of time I spent waiting near water holes – on the ground or up in the trees – trying to understand the animals’ behavior, is not common among researchers nowadays. They usually go by vehicles, they have proper data sheets based on which they collect data, and they’re very good in writing. Today, researchers are much more talented in quantitative ecology and, put together with their writing abilities, they’re able to write fantastic papers. But there is not much observation or understanding of natural history.

HS: One example of the use of natural history in this paper is in the identification of points safe from elephants from where to make observations. Talk a little bit about that.

AJTJ: My study area didn’t have many rocks; it’s not a very hilly area. In a hilly area you can sit on a slope and watch. In my study area, I had trees, many of which I could climb and sit safely on and make observations. Now when I go there and see the same trees, I wonder, my god, how did I climb them in those days? I used to walk only along the roads, so I can identify those trees today also when I go there. Some of the trees have died out.

You know, today, the regeneration of palatable species is exceedingly poor in places like Bandipur. It is degrading very fast. It is taken over by Lantana and Parthenium and Senna spectabilis. We’re helpless against it. The habitat quality is going down very fast.

HS: I wanted to ask you about this: you’ve been going back to Bandipur regularly over the years since this study was done. Like you just described, what changes do you notice from the time when you did this study?

AJTJ: There is enormous degradation. This Senna spectabilis was not there when I was doing this study. I wrote only about Lantana and Parthenium then. Later, I think some forest officer planted it in the Bandipur area, because it has spectacular flowers, and it spread. When I started doing my Western Ghats work after retiring from the Wildlife Institute of India (WII), which resulted in the book “Walking the Western Ghats“, I drew the attention of the forest departments to that problem. Nobody talked about it before that. I saw the problem of Senna spectabilis in Bhadra, I saw it in BRT, and I saw it in Nagarhole. It has taken over vast areas in Wayanad WLS. Now everybody talks about it. Once I gave a talk to the Tamil Nadu forest department staff in Sathyamangalam. The DFO [Divisonal Forest Officer] could not distinguish Senna spectabilis from Cassia siamea. What I’m saying is, if you don’t have the capability to identify a problem species, if you think it is part of the ecosystem, then the problem will continue. Senna spectabilis is worse than Lantana, and all the three southern states should work together to get rid of it from the forests as well as from outside forest areas. It should not be grown even in parks.

Part of the degradation has also been contributed by elephants; they have debarked lots of trees, as a result of which trees have died, particularly teak trees and so on. The problem is aggravated by the fact that there is not much regeneration of edible species in the forests.

HS: How has the wildlife in Bandipur changed over time?

AJTJ: Sambar number has gone down drastically. Sambar is very vulnerable to tiger predation. Dholes also prey on them. I always say sambar and tiger are made for each other. Both are large in size, crepuscular or nocturnal, always found in the forest. Sambar doesn’t have ‘yarding behaviour’, gathering in open areas to spend the night, as chital do. There was one [SG] Neginhal – he’s no more now – who wrote the first management plan for Bandipur Tiger Reserve. I remember reading through that long time ago, in which he said that in Bandipur, over an area of 800-900 square kilometer, there may be about 12-15 tigers. Today that number is over 100! If we include Nagarhole, together, these two parks have 250 tigers. In my opinion, as a result of tiger and dhole predation, sambar number has gone down very drastically. In addition to vulnerability to predation, sambar also have very little quality forage to eat. Once, when I went to Mudumalai and went for a drive, I asked an elephant mahout, what is this, we have not seen many sambar? He said, sir, what is there for them to eat? Everywhere there is only Lantana. Barking deer numbers have also gone down, I think. It is a territorial species. When predator numbers increase, they’re very vulnerable. In my opinion, chital, because of its habit of yarding in open areas, is able to survive and thrive.

HS: Why do you think tiger numbers have gone up so much?

AJTJ: In north India, along the border with Nepal, poaching is a big problem. They can easily smuggle the bones of the poached tigers across Nepal to China. Here in the south, our tiger population is fairly free from such poaching. As long as there is sufficient habitat, cover, water, lack of disturbance and enough food in the form of chital, sambar, gaur and some wild pigs, tigers will do well. Further, the Nilgiri landscape is part of a large (ca. 8000 sq.km) intact tiger landscape with the required density of wild prey, which also ensures a healthy population of tigers.

HS: What about dholes? How have they fared in Bandipur over time?

AJTJ: Dholes are very vulnerable to diseases. The first time we went there in 1974 , Michael Fox and I saw a pack of 19 dholes on the Sigur slope in Mudumalai, trying to attack a gaur calf. We later saw them on a big wild boar kill and once crossing the road. We even came across their defecation site. In 1975, when we went back there, there was no sign of that pack. Nineteen dholes simply disappeared. That’s one characteristic of dholes: their population fluctuates because of diseases they get, largely from free-ranging dogs, such as Canine Distemper, Mange, Rabies, etc. One field director in Kanha –A.S. Parihar, who is no more – told me that he once saw six dholes plunge into a waterhole and never come back out. Was it because of Rabies? They might have wanted to drink water but were not able to. I don’t know. When George Schaller studied “deer and the tiger” in Kanha in 1963-64 he never encountered dholes, but dholes are there now. So, diseases can have a big impact on dholes. Jackal number has also gone down drastically in south India. When I did my Western Ghats work with Raghu [R. Raghunath] from NCF, we drove 10,000 kilometers and walked 1300-1400 kilometers across the Western Ghats. Totally, we had only three sightings of Jackal; one in the Korakundah Organic Tea Estate in the Upper Nilgiris, and two near Anshi-Dandeli, now Kali Tiger Reserve.

HS: This paper has a very nice photograph of Jackal [Plate VI].

AJTJ: Very interesting. That picture was taken in the waterhole known as “Mysore Lodge Pickup” just in front of the VIP forest guest house in Bandipur. It was a small water body in those days, which they’ve now made into a big one. I was sitting among the bamboo on the ground. There was a Peahen at the edge of the waterhole. The Jackal came, and the Peahen stood, hackles raised, but the Jackal did not pay any attention to it. An enlarged picture of the jackal adorned the wall in Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc for several years. I am not aware of its fate now.

HS: Do you have any other anecdotes to share with us from your time walking in the forests of Bandipur?

AJTJ: I had nearly 10 sightings of tigers, all of which were either while walking or from trees. Each sighting was memorable, but I will talk about only two here. Once, while walking from Kolakmallikatte to Ministerguthi road, taking the short cut through the forest, I saw a 4-month old cub crossing the road when I just reached the edge of the road. Immediately, I sat at the base of a tree and tried to take out my camera, which was in a plastic bag in my rucksack, when I saw one more cub crossing the road. Soon, the mother came on the road and, when she heard the rustling noise I made while trying to take out the camera, looked in my direction. Although the tigress was about 50m away it was an unnerving experience and I froze. Possibly the attention of the tigress was more on the cubs and so she failed to see me and followed the cubs into the bush.

Next day morning, with the local forester, Jeyandrappa, a tall and well built man, I went along the road looking for signs. In one turning, the tigress, which was possibly coming with the cubs, charged me with a terrifying roar like a red Bullet motor cycle, may be from a distance of 20-30 m. Because I was bending down while walking, the roar felled me to the ground, but the tigress went back as fast as it charged.

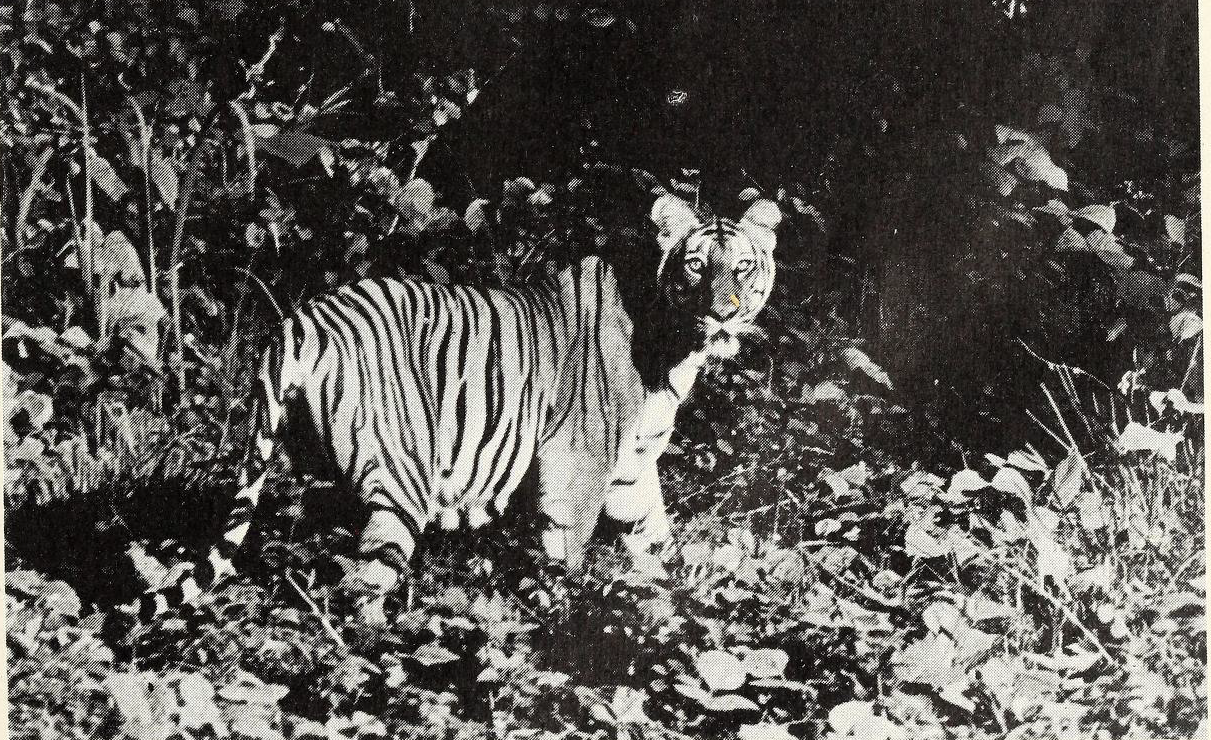

While working in Bandipur, I found out that no one had taken a picture of a tiger in the Reserve. So, I decided to take a picture. I selected a mango tree, ca. 2 km from Bandipur, in Ministerguthi nallah, which reeked with the smell of tiger spray and had a straight bole for about 5m. Whenever I had a free morning (when a large kill is made and the dholes have eaten well, they don’t hunt the next day, and so my morning was free on such days), using a rope tied to a branch up in the tree by Keechanna, I used to scale up the tree and wait there for 2-3 hours. The memorable day came on 23rd May 1978, around 0730 hrs. The picture of the tiger I took that day can be seen in plate V of the paper. Late N. Sunderraj, a friend of mine from Bangalore had given me a 100 ASA film which was used to photograph the tiger, and so large enlargements of the picture can be made. One such enlarged picture can be seen in the WWF-India Guest Room in New Delhi, thanks to Mr. Ravi Singh, Secretary General and CEO, WWF-India. Possibly, it is the first best tiger picture ever taken in south India.

HS: Were you interested in photography from earlier, even before you started your PhD?

AJTJ: Yes.

HS: There are so many lovely photographs in this paper.

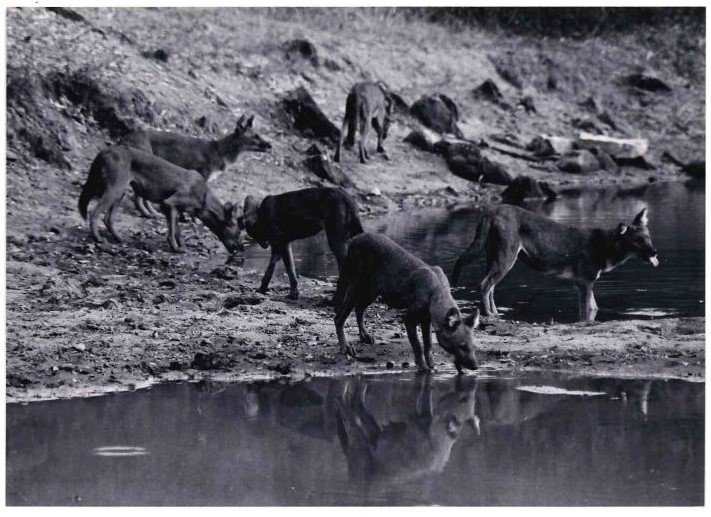

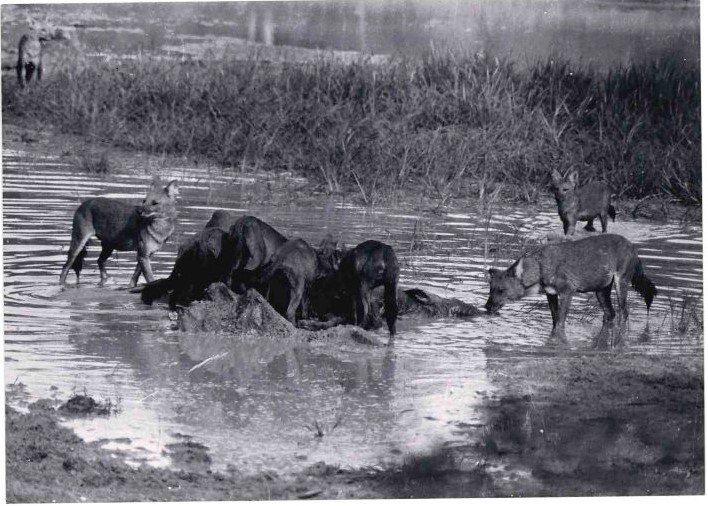

AJTJ: For this one [Sambar-Dhole interaction; Plate VI], I was up in a Rosewood tree. In those days in Bandipur, they used to cut view-lines in the large Lantana patch near Thavarakatte in which the Mysore maharaja had his shooting hide. In the bygone past, when the maharaja was hunting tigers, his staff would tie a bait for the tiger, and when the tiger made the kill, message will be sent to the maharaja, who will then come and sit in the hide. The staff would then, with the help of elephants, drive the tiger towards the hide and the maharaja would shoot the animal. That shooting hide was still there when I was doing my field work. There was also a beautiful Terminalia bellirica tree nearby. Sometimes, I’d sit inside the shooting hide. Or when elephants came closer to the fragile shooting hide – it was close to Thavarakatte – I would climb the bellirica tree and wait. That tree has gone now. Earlier, in the view-line, they used to put fine sand and so you could see the pugmarks; now such management has gone. Last time when I visited Bandipur, in April 2022, there was only a tag on a tree near the place where the shooting hide was present with a label “shooting box”. I would say that one major reason for the decline in the management efforts seen in the 1980s is that the Kurubas are no longer living in Bandipur. Now, for any work in the Reserve, the management has to bring labourers from outside. Like working in office, they come at 9 am and leave by 4 or 5 pm. So, that type of intensive management is not there anymore. Earlier, when the Kurubas were living in Bandipur, they would work almost the whole day. Coming back to the photo, there was a dhole hunt happening, so I went and climbed the Rosewood tree to watch. Then the dhole pack size was 15. I noticed that some dholes (6-7) stood on the view-line excitedly watching the Lantana patch in front where other dholes were flushing out the sambar. I became so excited that I blew into the viewfinder; that’s why the picture is not very clear! And do you notice the behavior of sambar? Inflated nostrils, erect pinna, erect mane, eyes rolled back so that the white was visible, making a strong exhaling sound and stamping the forefeet. The dholes simply walked away; they didn’t attack! Three sambar came, seven or eight dholes were there, a few more were behind and inside the bush also, but they didn’t pursue the attack.

This might be because chital is so easily available in Bandipur, and easier to bring down compared to sambar. Later, still up in the tree, I heard the same pack killing a chital. In a place like Periyar, dholes will not give up so easily because sambar is the main prey; no chital there.

HS: The paper contains a lot of natural history information on anti-predatory behaviour. Was that something that came up through your observations during the study?

AJTJ: Ya, ya. For example, sambar baying in water. If the water is not very deep, such that the sambar can stand, but deep enough that dholes need to swim, sambar can keep away a dhole pack by rising on their hind legs and beating the water whenever the dholes come near. In a shallow pool, two sambar standing rump together can keep away a dhole pack. But this will not work in Periyar lake because, when the sambar are forced into deep water, they will not be able to use their forelegs. And the dholes swim well. One dhole will go closer to the sambar, catch the nose of the sambar and drag it to the shore where other dholes will join in the attack. Often the larger prey are killed by disemboweling and that is the reason dholes got the name “cruel killers”. They do not have the killing bite of a large predator, say a tiger.

HS: Are these the first time such anti-predatory behaviors were described?

AJTJ: North American deer species like elk and moose also run into water when chased by wolves. But for sambar, this might be the first description.

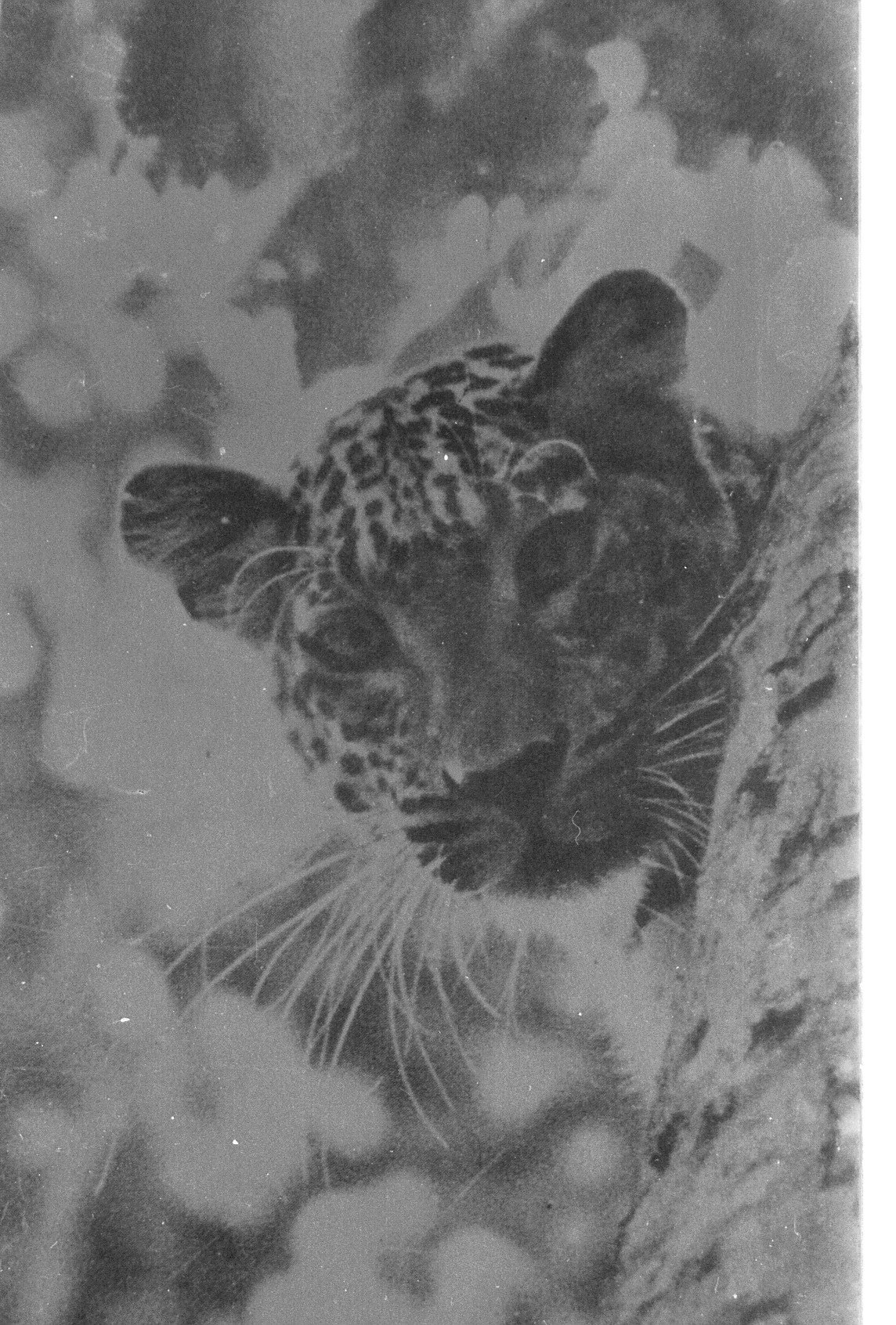

HS: Tell us the story behind the leopard photograph in the paper

AJTJ: One day, near Thavarakatte I smelt a kill. This is one thing I used to tell our students and forest officer trainees in WII: when you’re in the forest, all your senses – eyes, ears and nose – should be alert. We found that a big Chital stag had been killed and partly eaten. One of my assistants said, sir, when we went there, we saw a tiger running away. So I said, okay, let me wait for the tiger. At that time, Thavarakatte had a dense growth of big bamboo the regeneration of which, after flowering, sadly, has failed. I climbed a tree carrying my rucksack with my camera, and told my assistants to drag the kill to an open area closer to my tree for better visibility. When they were doing this, one of my assistants said, sir, look behind. A leopard was in another tree, sitting and watching me! Possibly, the leopard also had climbed the tree to avoid the tiger. I turned around and took this picture. After some time, the leopard got down and walked away and as it was walking away, some Sambar that were nearby gave very subdued alarm calls. They probably knew that the leopard was not hunting.

HS: How far was the leopard from you when you took the photograph?

AJTJ: Not far. Maybe about 20-25 feet away.

HS: Another interesting aspect of this paper is the table in which you compare leopard, tiger and dhole [Page 41].

AJTJ: I will say that is a very important contribution: the ecological and behavioral isolation of the three predators. I think that table has got good information. For example, how the leopard, in comparison to the other species, has the ability to climb trees, can survive on smaller prey, can live in areas of sparse vegetation etc. That is one of the important contributions from this paper.

HS: Based on this comparison, you conclude that leopards are more likely to be able to survive in disturbed habitats compared to dholes or tigers. Is that your opinion even now?

AJTJ: Yes. Mass deaths due to disease, which has been seen in dholes, has not been reported in leopards or tigers. That makes dholes very vulnerable. That’s the reason there is a lot of fluctuation in the dhole numbers, which does not happen with the tiger and leopard.

HS: What do you see as other important contributions of this paper?

AJTJ: The information on the yarding behaviour of chital. If you want to maintain a high density population of chital in an area, you need meadow-type of habitats for them: some water, good protection – an anti-poaching camp can be there – and the meadow habitat should not be allowed to be overgrown with Lantana and other weeds. If you have such habitats throughout the reserve it’s possible to increase the chital number. Such places will be used by chital for yarding at night where they will be immune to stalking predators like leopard and tiger which have to go closer to group to make a kill. While yarding, chital look in different directions and can easily see a predator approaching and then all of them together give the alarm call as if telling the predator that we have seen you. This behaviour, invariably, would discourage the predator from pursuing the hunt. This, I would say, is an important observation from this paper.

HS: At the time of this study were you already interested in observing and identifying plants?

AJTJ: Again, you know, I was taking some cues from Schaller’s book about the importance of understanding the vegetation. During my study, I knew a few things about plants, such as, Terminalia bellirica is very important, Terminalia tomentosa is very important, and Lantana is bad. There is a plant called Randia dumetorum whose fruits are eaten a lot in the winter by chital. Whenever there was a fresh kill of an animal we would open it up to see what it had eaten. We often found Amla and Randia fruits in chital stomachs. From this we come to know that, in the winter, fruits become very important in the diet. I even wrote a short article about the importance of fruits in the diet of chital, which was published in JBNHS [(1981) 78: 594-595]. Soumya Prasad once told me that that paper gave her some ideas for her work.

HS: Another interesting natural history observation in the paper is about using Jungle crows to locate kills. Talk a little bit about that.

AJTJ: In Bandipur, interestingly, jungle crows used to follow dholes, probably because they know there will be a kill soon. From my observations, I felt that the crows used to wander, one flying here and one flying there and if they saw a tiger in the bush they’d become suspicious. And then, if one of them located a kill they would call all the others. You know, when I went to Dehra Dun and started working in the goral areas in Rajaji National Park, I found that the people who came to cut Bhabar grass were also stealing kills, and they would locate the kills with the help of jungle crows. They used red-billed blue magpies also to locate the kills. Stealing kills by the grass cutters almost all through the winter was the major reason for the decline of tiger number in Rajaji National Park, west of Ganges.

HS: How did you make the maps for this paper?

AJTJ: I don’t remember. It may not be very accurate. I don’t know how I made them.

HS: When you were writing, did you use a typewriter?

AJTJ: No, no, it was all handwritten. I used to write and send drafts to Daniel and Madhav Gadgil.

HS: You mention a person by the name of T Gopal in the Acknowledgements for help in typing out the manuscript.

AJTJ: [Laughs] Very interesting. He was a typist in the college in Sivakasi where I was teaching, and where I went back after this study. Gopal would type out my handwritten drafts. Once, in one place, I wrote “Dholes do not cache their prey”. Gopal came and asked me, what sir? You don’t know the spelling of “catch”?! He did the typing, and then we cyclostyled it and made 25 copies of that thesis and gave it to different people, including WWF-India, IISc, WII and so on.

HS: What was the role of John Seidensticker?

AJTJ: He was my guru in Front Royal. I studied raccoons and opossums under his guidance. He’d earlier studied tigers and leopards in Nepal; Mel Sunquist also had worked in Nepal. We were all living as a community there in Front Royal. It was very nice. Mel and Fiona were our neighbours for a short period of time. Once, Fiona was going to Nepal for a month, so she asked my wife if she can cook for Mel because otherwise he wouldn’t cook and eat and will starve. So, for almost one month, Mel was eating in our house every day. Dr. John F. Eisenberg used to come to Front Royal and do his own trapping for rodents. He and Devra Kleiman (his wife then) had small Sherman traps. They would put peanut butter as bait, catch the rodents, do toe clipping and then they would wash the traps and keep them ready for the next weekend. Eisenberg used to say, you may be guiding many students but you should always have your own small research. That was his attitude. A good number of people in Front Royal came and ate in our home and they all enjoyed the South Indian chicken, mutton and fish curries my wife cooked.

When I was in the US after submitting my thesis, Madhav Gadgil visited the Smithsonian Institution. Eisenberg wrote up a report about my thesis, which Madhav Gadgil signed and sent to the university saying that I should be awarded the degree. Nothing happened. We sent it to the registrar, the vice-chancellor, everyone. Nothing happened. They said I had to come to Madurai to attend the viva. I came back to India, and six times I went to Madurai asking them to conduct the viva. Finally, they called late MD Parthasarathy, who studied primates, as the examiner and to conduct the viva. He asked me only one question: Can leopard and dhole live together in the same forest? I answered and the viva was over. I was awarded the degree. Had I been awarded the degree while in US I may have got a job and stayed there. Eisenberg was one of the most noble and kind-hearted people I have met in my life. He told me, Johnsingh, if you get a job and live in US you will be one among the thousands, but if you go back and serve in India, you will be one among the ten. Once, he came to Wildlife Institute of India on an assignment when I was serving there and he came home for dinner. By that time, my elder son Mike Johnsingh had gone to National Defense Academy and my younger son Mervin Johnsingh, about eight years old, was at home. Eisenberg took Mervin’s hand, told him, I am your father’s friend, and asked him, Can I kiss your hand? Mervin nodded and he kissed his hand.

HS: Did all the writing for this paper happen when you were in the US?

AJTJ: Yes. Before that, I had written my thesis. In the US, when writing this paper, Fiona helped me.

HS: It’s so well-written and easy to read. Anything else you remember about the writing?

AJTJ: John Seidensticker used to say, write, read it, read it again after three or four days, and if you’re not able to make any further improvement give it to somebody to read. That was good advice. All my schooling was in Tamil-medium, so, even now, I don’t feel confident about my English and that is the reason why I usually give whatever I write to someone to read and provide feedback.

HS: You write so well, both in your scientific papers as well as in your articles for a general audience. When you read this paper now, did anything catch your attention or did anything strike you?

AJTJ: I felt that, okay, my God, even in those days I did an okay job!

HS: How did you decide to submit this paper to JBNHS? Did you consider any other journals?

AJTJ: No, no, John Seidensticker suggested we should submit to JBNHS because it would be useful for other Indian scientists. He was right. I wrote another paper on Dhole that David Macdonald kindly helped me publish in Journal of Zoology [1982, 198:443-463]. I spent a week with him in Oxford when returning from US, along with my wife and my elder son, Mike. Thanks to David.

HS: After your 1983 paper was published, was there any feedback of any sort?

AJTJ: In those days, not many people would have had the capability to evaluate even.

HS: This is a single-author paper. At any point was there any discussion on whether it should include any other authors?

AJTJ: No. But, you know, based on the six months of work with Michael Fox, I wrote a paper and sent it to JBNHS, which got published [Fox & Johnsingh, 1975, J.Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc.72:321-326]. Michael Fox later told me, you should have shown the manuscript to me before you sent it!

HS: Do you think this 1983 publication had a role in shaping your career?

AJTJ: I don’t think so. When I came back from America, BHNS [Bombay Natural History Society] employed me to lead an elephant project, with late Ajay Desai and [N] Sivaganesan as researchers. There again Daniel, who was at BNHS, played a role. Then for Wildlife Institute of India, I simply got a letter from the ministry, without an interview or anything, saying that I had been appointed as deputy director of the institute, and asking me to come and join. People had heard about me and seen me working in Bandipur. So, there was some knowledge about me, you know. That was probably why I was offered the job.

HS: Is this one of your favourite papers?

AJTJ: It is very important. John Seidensticker said that this paper will be very valuable for a long time. Now, when you’re asking these questions, probing me to think about it more, more people may look at it again much more carefully!

HS: When you read it and look back now, do you wish you had done some things differently?

AJTJ: Like I said earlier, Rauf Ali suggested doing a nice grid-based statistical analysis. Maybe I should have done it. But you see, I couldn’t have done that on my own; I needed somebody like Rauf or Joshi to help me. Similarly, I was doing these eight transects every month. Had anyone suggested to me that I have a description of the vegetation and terrain and more information about the sightings, it is possible I would have got nice information for some density estimates. But these are all after thoughts, you know; crying over spilled milk.

HS: Final question: If there was a young student who is about to read this paper today, what might you say to them to guide their reading? Would you add any caveats they should keep in mind when reading this paper?

AJTJ: No. I would ask them to read it, and when reading it to imagine me working there, on foot, more than 40 years ago. And I would ask them to try not to find fault with it, because you can easily find fault with it, in retrospect.

0 Comments