In a paper published in Ecology in 1985, Lenore Fahrig and Gray Merriam presented a model for changes in population sizes in a set of interconnected patches, which predicted that populations in isolated patches will grow at a slower rate and are thus morel likely to go extinct than those in connected patches. Fahrig and Merriam found support for the predictions of their model, when they tested it using data from white-footed mouse populations in woodlots in an agricultural landscape in southeastern Ontario, Canada. Thirty three years after the paper was published I asked Lenore Fahrig about how she got interested in this topic, her memories of field work, and the impact of this study on her subsequent research.

Citation: Fahrig, L., & Merriam, G. (1985). Habitat patch connectivity and population survival. Ecology, 66(6), 1762-1768.

Date of interview: Questions sent by email on 22nd January 2018; responses received by email on 12th February 2018.

Hari Sridhar: This paper is based on a project you did for your Master’s dissertation. I would like to start by asking you how you chose to work on this topic for your project, this interesting mix of mathematical modelling followed by a field test. Also, is the content of the paper identical to the dissertation, or did you include some extra work in the paper?

Lenore Fahrig: Yes, this paper was based on my MSc thesis. When I began my MSc thesis I already knew I was interested to learn how to do simulation modelling and also I was already interested in spatial ecology. These interests developed during the fourth year of my BSc.

The paper is a subset of my MSc thesis. Apart from the work presented in this paper, the thesis also contains a nonlinear regression analysis to estimate recruitment rates (p. 39-44). This part was never published. It also contains an extension of the model (p. 58-64), a version of which was published in Ecological Modelling.

HS: Gray Merriam is your co-author on this paper. Could you tell us how this collaboration came about and what did each of you bring to this paper? Also, how did this collaboration work, i.e. did you meet often to develop the model? Did Dr. Merriam participate in the field work?

LF: Gray Merriam was my MSc thesis supervisor. He had experience working with Peromyscus leucopus which is the reason I selected that species for the field study. Gray had recently coined the term ‘habitat connectivity’ and he was very interested in the role of hedgerows in connecting populations living in woodlots. He was instrumental in helping me design the field study. Gray had lunch with his lab every day, so lunchtime was always a good time to talk about my project if I had any issues. I did the field work by myself. Gray introduced me to Len Lefkovitch who was a researcher in the government. Dr. Lefkovitch helped me to build the simulation model and he was my main advisor on that part of the project. He also taught me the necessary statistical methods for my study.

HS: In the paper you list three reasons for choosing to test this model using the white-footed mouse. I would like to know a little more about your own encounter and engagement with this species. Was this project your first encounter with this species? Did you consider other species to test the model on? How long after this study did you continue to work on the white-footed mouse?

LF: This was my first encounter with this species. As mentioned above, I selected it because my thesis supervisor, Gray Merriam, had worked with this species before. Before my MSc, I had worked on lichens in my BSc thesis, and after my MSc I worked on a butterfly species in my PhD thesis. Over the past 27 years as a professor, my graduate students have worked on a wide range of species including plants, insects and other arthropods, birds, various mammals including bats, amphibians, reptiles, and even a virus. A few of my graduate students have worked with the white-footed mouse.

HS: You did field work from the 2nd week of June to the first week of September 1982 for this study. When you think back to that period, what are your most striking memories of field work? Do you remember what your daily routine was? Did you work along or did you have help in the field? etc.

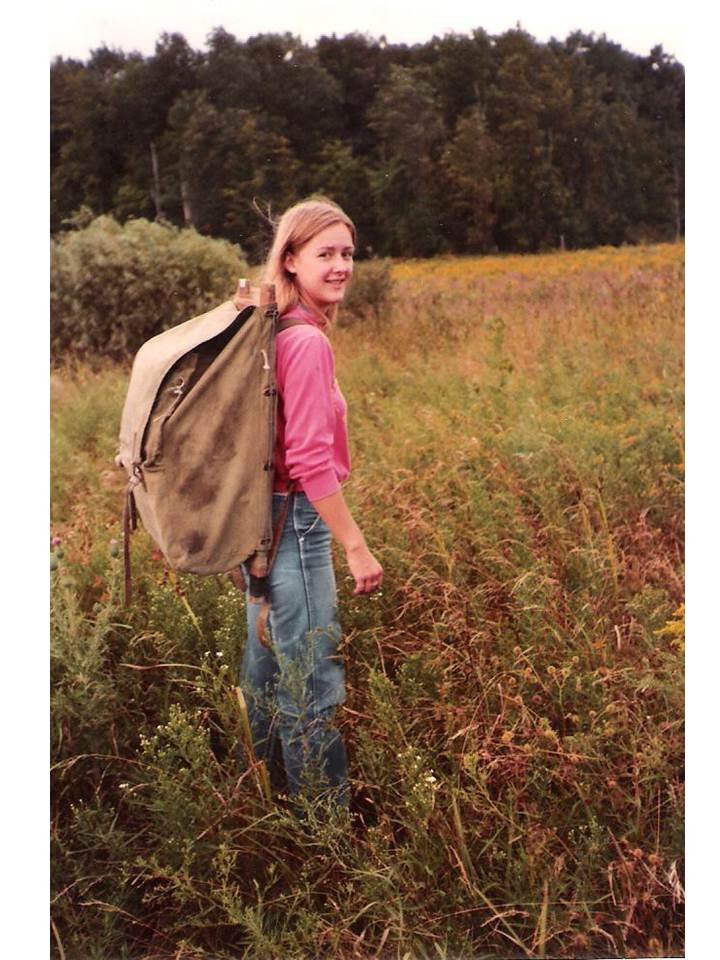

LF: I remember on the first day of fieldwork I had failed to take insect repellent with me. As soon as I entered the first forest patch I was ambushed by mosquitoes so I had to make a hasty retreat to get better prepared. I remember that I really enjoyed being in the woods by myself early in the morning. I remember climbing over fences with a backpack full of field gear. I worked alone except for one day during the trapping period when my sisters were in town and they wanted to come with me. That was a bad idea. I was doing the removal experiment for recruitment estimation, which meant I had to move the captured mice to another woodlot several km away. My sisters seemed incapable of opening a trap without letting the mouse go, so this created a bit of a blip in my data.

Lenore Fahrig during field work in the summer of 1982 (© Judith Carson)

HS: You say “To apply the model to P. leucopus, aging rates through three age classes, weekly birth and death rates, and weekly, age-specific movement rates were estimated from detailed studies in the literature”

Do you remember how challenging it was (before the time of easy Google searches) to search and extract this information?

LF: Yes, it was challenging, but on the other hand, there were many fewer papers in the literature back then than there are now. During my BSc I learned how to use BioAbstracts (on paper) to do a search, so I used the same approach for my literature searches during my MSc. I was lucky to be in Ottawa, because I could go to the National Research Council library which had virtually every journal I could hope to find. They also had nice quiet research rooms. I could select a room, take in a pile of journal volumes, and if I didn’t finish with them that day I could leave them there until the next day when I could go back and continue my search. This made the literature search very efficient.

HS: The field study was conducted in a set of woodlots near Ottawa. Would you remember how you decided to do the study in this location? When was the last time you visited these woodlots? In what ways have they changed from the time you worked there for this study? Are the mice still there?

LF: I did the study near Ottawa simply because that is where I was living. I found the woodlots by scanning air photos. The biggest challenge was to find the isolated woodlots. I have not been back to the woodlots since the study.

HS: You use a method you call “Smoked paper tracking” to sample mice populations. Could you tell us a little more about how you developed this method, and whether you still use this method today?

LF: The idea was to put a layer of black carbon onto the paper, so that when the mouse ran through the tube it would pick up carbon on its feet and leave white footprints on the black paper. At the time I used a very unhealthy method in that I held the strips of paper over a benzene flame to make them black. We don’t use that method anymore. More recently my students mix carbon black with oil and paint it onto a piece of waxed paper. They staple this paper onto a larger white paper strip so that the animals walk across the waxed paper and leave black footprints on the white paper (Rytwinski and Fahrig 2011 is an example of the use of this method).

HS: You acknowledge L.P. Lefkovitch at the end of the paper. Could you tell us a little more about who this person was, how you knew him, and how he helped in this study?

LF: Dr. Len Lefkovitch was a biomathematician who is best known for introducing the “Lefkovitch matrix” in his paper “Study of population growth in organisms grouped by stages” in 1965 (Biometrics 21).

HS: How long did the writing of this paper take? When and where did you do most of the writing?

LF: I don’t remember exactly but I would guess about 4 months. I worked mostly alone in my apartment late at night.

HS: Did this paper have a relatively smooth ride through peer-review? Was Ecology the first place this was submitted to?

LF: Ecology was the first place I submitted it to. I remember it took a long time to get the reviews back because the editor moved and the paper was misplaced for a few months. I submitted it in 1983 and it was published in 1985. In retrospect I would say it was a fairly smooth ride though.

HS: The broad topic of this paper – habitat patches and connectivity – has remained a life-long research interest for you. Could you reflect on the impact of this initial investigation, on the choices you made in your career subsequently?

LF: As I mentioned above, I became interested in spatial ecology in general, and particularly in spatial heterogeneity, during the last year of my undergraduate degree. I think the biggest impact of my MSc on my research career was the modelling piece. While the field work was at a patch scale (i.e. each patch = one data point), the modelling work that followed was at a landscape scale (i.e. each group of patches or landscape = one data point). This increase in scale set the stage for my later work in investigating the independent effects of habitat loss and fragmentation, a question that can only be addressed at a landscape scale.

HS: This paper has been cited over 900 times. Do you have a sense of what it mostly gets cited for?

LF: No; I haven’t looked into that.

HS: Today, 32 years after it was published, could you reflect on the main conclusion of this paper:

“The model prediction that P. leucopus populations in isolated woodlots have lower growth rates than those in connected woodlots is supported by the field results (F = 4.795, P < .05). As stated earlier, this has important implications for the population survival of P. leucopus in fragmented habitat. If populations begin the breeding season with only a few females, and if isolated populations have lower growth rates, they will begin the winter with fewer individuals. The extreme overwintering mortality at our latitudes means that isolated populations have higher probabilities of be- coming extinct before the next breeding season. Re- establishment of extinct local populations will take longer in isolated patches than in connected ones. In a whole region, therefore, the frequency and persistence of local extinctions of P. leucopus populations depends on the degree to which individual patches are isolated from one another.”

LF: I think the conclusion is still correct.

HS: Have you updated this model in anyway subsequent to this paper? If you did the field study today, what would you do differently?

LF: A subsequent student, Kringen Henein, working with Gray Merriam, studied an altered version of the model. The paper was published in 1990 (Landscape Ecology 4:157-170).

HS: In concluding the paper you say: “Although the model has been applied to P. leucopus in woodlots, it may be a useful tool for predicting changes in the population dynamics of any of the many organisms that are found living in habitat patches.”

Could you comment on the use of this model on other organisms, subsequent to this study – to what extent has that happened, are findings in other systems congruent with your findings etc.?

LF: Other than the paper mentioned above I don’t think this particular model was used on other organisms, at least not that I know of.

HS: Have you ever read this paper after it was published? If yes, in what context?

LF: I don’t remember.

HS: Would you count this paper as a favourite, among all the papers you have written?

LF: On a person level it certainly has a strong nostalgic appeal.

HS: What would you say to a student who is about to read this paper today? What should he or she take away from this paper written 32 years ago? Would you add any caveats? Would you point them to other papers that they should read along with this?

LF:

On landscape connectivity they should read: Tischendorf, L. and L. Fahrig. 2000. How should we measure landscape connectivity? Landscape Ecology 15: 633-641.

On habitat fragmentation they should read: Fahrig L. 2017. Ecological responses to habitat fragmentation per se. Annual Reviews of Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 48:1-23.

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks